Danie Steel, Sydney Cole Alexander, Martin K. Lewis, Alex Herrald, Hunter Canning

by Samuel L. Leiter

In a script note for his stumbling satire on our racist history, The American Tradition, Ray Yamanouchi asks directors to “utilize verfremdungseffekt (alienation),” by which he means Bertolt Brecht’s theory that calls for production methods designed to insure that the audience is thinking about what they’re watching. Regardless of how one interprets Brecht’s concept, and there have been multiple explanations, the great German dramatist/theorist/director didn’t intend his “alienation” effect to actually alienate anyone. That may not be how you feel after viewing Axel Avin, Jr.’s, unsubtle staging for the New Light Theater Project.

Winner of the 2018-2019 New Light New Voices Award, Yamanouchi’s is the third—and weakest—Off-Broadway play of the past two months to dwell on the institution of American slavery, the others being Slave Play and Behind the Sheet. Staged in the cramped confines of the funky 13th Street Repertory Company, The American Tradition has a rather far-fetched but potentially engaging premise. It imagines that a pair of black slaves—a quadroon woman, Eleanor (Sydney Cole Alexander), fair-skinned enough to pass for white, and her dark-skinned husband, Bill (Martin K. Lewis)—escape their antebellum plantation by train en route to Pennsylvania. Eleanor cross-dresses as a white slave owner named Evander, while Bill fakes being her faithful slave-servant.

Sydney Cole Alexander, Hunter Canning

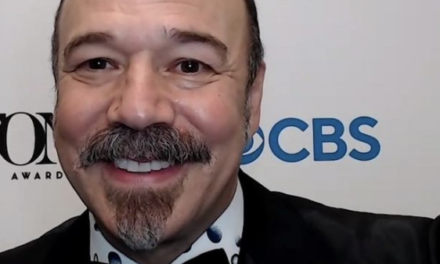

The trip gets the pair entangled with an alcoholic slave owner named Walsh (Alex Herrald), who easily accepts their impersonations and who tries to convince Evander to join the Not All Slavers organization. According to one of its leaders, Henry (Hunter Canning), its members are supposedly enlightened slave owners who profess that the best way to preserve slavery is to treat their charges humanely. When Walsh eventually recaptures one of his own runaways, Rose (Danie Steel), we see just how deeply he believes that.

Complicating matters is the revelation that the Not All Slavers group is somehow also a deregulatory, free market, pro-slavery, not-for-profit institution called the National Institute for Economic Prosperity. This is a supposedly satirical development that even the characters declare confusing. Yamanouchi makes little attempt to clarify its place in the play even though the last words we hear are in a long speech about its tenets.

The other significant white man Eleanor/Evander and Bill encounter is Buckley (Canning again), the train conductor, who comes to the aid of the endangered slaves because he happens to be a member of the Abolitionists of America. The mere saying of that name always inspires his right fist to shoot up in a running joke reminiscent of Peter Sellers in Doctor Strangelove struggling to prevent his arm from rising in the Nazi salute. If this is a hint at Buckley’s unconscious racism, it falls flat.

Yamanouchi’s inherently melodramatic play isn’t intended to be taken literally. Slightly reminiscent of Branden Jacobs-Jenkin’s far superior An Octoroon, it’s far less inventively produced, with thematic points that are neither new, revelatory, or especially convincing. One, for example, is the idea that, given the chance, seriously mistreated slaves wouldn’t take revenge when the opportunity arose. Whatever the play’s thoughts, they aren’t particularly well conveyed through Yamanouchi’s cartoonish characters, barely funny japeries, anachronistic language and props (like a semi-automatic pistol), and a torrent of four-letter words.

Alex Herrald, Martin K. Lewis, Hunter Canning

Director Avins’s “alienation” approach is embedded in a minimalist production. The cast of five is visible throughout on a set designed by Brian Dudkiewicz to look like walls of red, white, and blue brick, with a single entrance and a row of upstage metal, straight back chairs. Elaine Wong’s varied lighting effects and Samantha Rose Lind’s simplified period costumes are satisfactory, while Enrico de Trizio’s diverse sound and music design adds considerably to the ambience.

The actors, all of them qualified pros, gamely follow Avins’s baton in speaking at the tops of their lungs at Mach speed. The approach may not make any of them convincing, nuanced, or interesting, but they have an unintended alienation effect. And Yamanouchi’s ending, with its ambiguous attempt to thrust the story into present day terms, only alienates us further.

The American Tradition. Through February 16 at 13th Street Repertory Company (50 West 13th Street, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues). www.newlighttheaterproject.com

Photos: Jody Christopherson