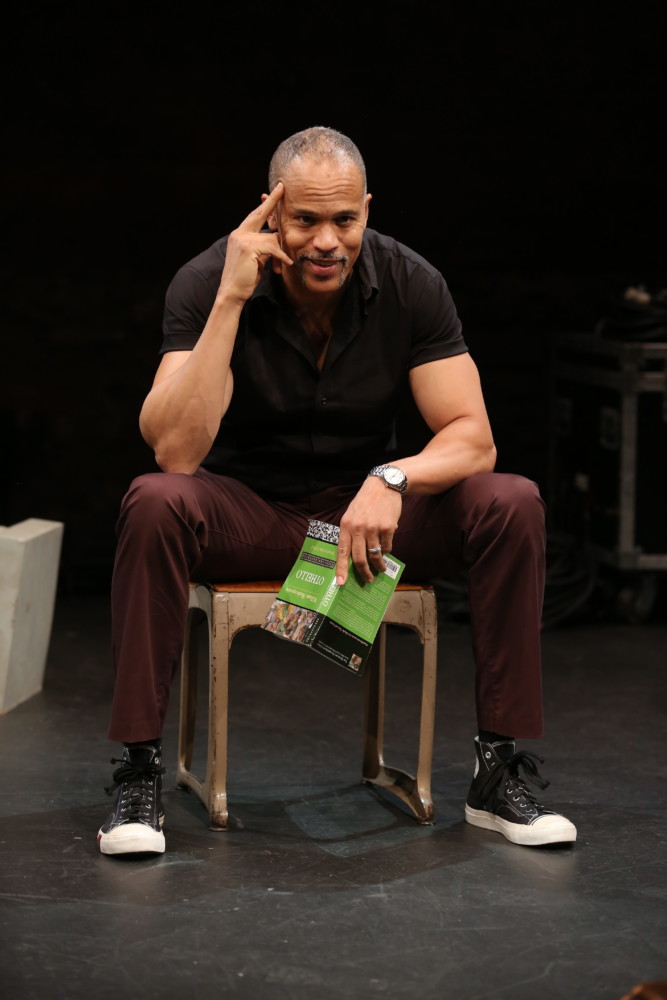

Basil Rodericks, Andy Baldeschwiler, Sara Hymes

By JK Clarke

I find it hard to understand why William Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well is so seldom performed. When done as elegantly as Hedgepig Ensemble’s recent, very brief, run at the Gene Frankel Theatre it’s as inviting as any of Shakespeare’s major comedies. Though considered a “problem play”—one characterized by ambiguity and flecked with tragic notes, making it not quite a pure comedy—it’s full of snappy dialog and a complex enough story that creates genuine anticipation. My only regret, and it’s a significant one, is that this production only played for two weekends. Local Shakespeare fans—particularly those who have been searching for an opportunity to see this play—were unlikely to have caught it.

The central storyline of All’s Well That Ends Well is the age-old canard: “if you relentlessly pursue the object of your desire and employ deceitful tactics, said person will eventually fall for you.” It’s a trope that’s been used and re-used in rom-coms—literary, cinematic and theatrical—for time immemorial and has always felt . . . well, inappropriate, and not solely because it encourages stalking. Ordinarily in such tales, the object of desire is a woman and the protagonist is an unexpectedly likable young man. What’s novel about All’s Well is that the script is flipped, making the pursuer a young woman, Helena (Sara Hymes), who’s a ward of the Countess (Desiree Baxter) and thus of a lower social class; and, of course, she’s in love with the Countess’s son, Bertram (Martin Lewis).

Desiree Baxter

Helena, played as delightfully adorkable and heartsick, is the daughter of a renowned, and recently deceased doctor. When lovelorn Helena, puppylike, follows Bertram to the court of the King of France (Basil Rodericks), she ends up being able to use her father’s leftover medications (and her previously concealed medical knowledge) to cure the king of a (possibly imagined) mortal illness (he’s a bit of a drama king). In gratitude, he offers her the right to choose any man in his court as her husband. Naturally, she picks Bertram. But he’s not only not attracted to her, but seems repulsed, and opts instead to join the military and departs immediately to fight in the Italian wars. And though the King has forcibly married the two, Bertram lays impossible conditions (primarily that she becomes pregnant by him, which is difficult in light of the fact that he refuses to stay with her) for the two to live as husband and wife.

In Italy Bertram is quite the player, seducing the locals with abandon. But Helena has followed him there, as well. And when she meets a girl he is wooing à la John Cusack in Say Anything (with a boom box lifted above his head), she conspires with the woman to swap places with her so that she may consummate the relationship. After further subterfuge, including faking her own death, she confronts Bertram before his mother and the King, whereupon he relents, seeing that she has endeavored so greatly to meet his conditions and win his love.

Elizabeth C.J. Roberts, Kariana Sanchez

Obviously there is a lot of implied behavior and thought in this play, and enormous room for interpretation and dramatic commentary. Just the question alone of why the very kind and sweet Helena would still want to marry such a jerk allows for all sorts of latitude and humor. Accordingly, Hedgepig’s production has a great deal of fun with it. Bolstered by terrific acting, it makes for an absolutely delightful comedy. Basil Rodericks as the French King is utterly charming, magnanimous and smooth in his mid-20th century purple velvet suit (Jamie Gross’s costumes are sublime, particularly when it comes to the king’s wardrobe) that bring to mind more lounge act than Loire Valley. His chemistry with Sara Hymes is sublime. She catches every nuance of Helena without making her obnoxious or creepy (which, by today’s standards, she certainly could be), and brings out all the humor and romance of her Helena. Desiree Baxter’s Countess is stately and elegant, due in part, no doubt, to Baxter’s extensive background in opera. And Andy Baldeschwiler is wonderful as LaFeu, the noble who represents the backbone of reason throughout the story.

The production crew—particularly Anna Driftmier (set) and Charlotte McPherson (lighting), and Carsen Joenk’s sound design featuring melancholic strains of Erik Satie that provide both a classical and contemporary feel—should be called out for their ability to take a small stage in a cramped theater just off the Bowery and create a very professional looking production that unfortunately played only briefly (the amount of work involved can only be deemed excessive for so short a run). I can only hope the show is somehow remounted elsewhere in the near future. More people deserve the chance to see this enchanting production of a seldom seen play.

All’s Well That Ends Well. Presented by Hedgepig Ensemble. Ran from December 6-15 at the Gene Frankel Theatre (24 Bond Street between The Bowery and Lafayette Street). www.hedgepigensemble.org

Photos: Allison Stock