Erin Treadway

In Space, everyone can hear Molly scream.

by JK Clarke

Society’s fascination with outer space is well documented, and has been since long before the first rocket ship exited the atmosphere. The exploration of deep space is a frequent subject of both television and film, the histories of which are dotted with classics, from one of the very first moving pictures ever made, George Méliès’ groundbreaking 1902 film, A Trip to the Moon, to the campy but thrilling 1950s sci-fi movies to the seemingly endless cycle of Star Wars films. But one would be hard pressed to recall noteworthy or memorable theater pieces about voyages into the great extraterrestrial expanses. Which is one of many things that makes Spaceman, now playing through March 9 at The Wild Project, all the more compelling

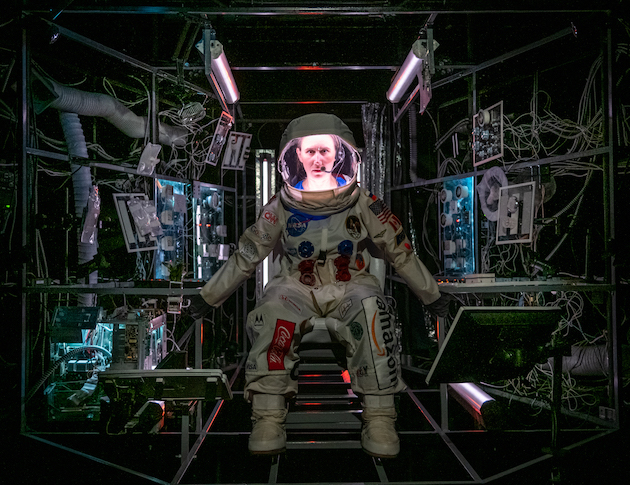

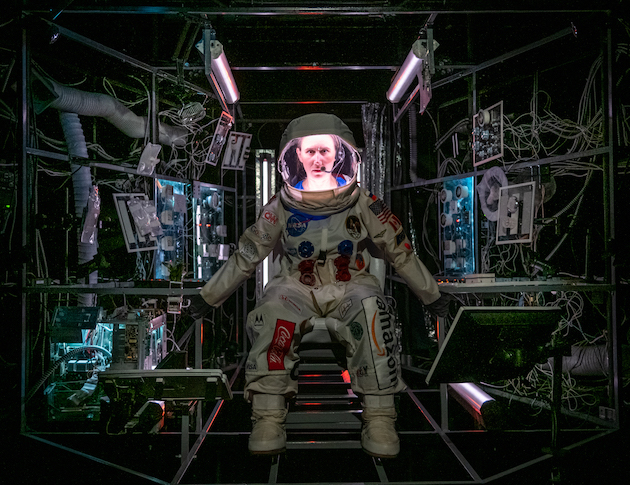

When you think about it, it’s inevitable that even the most romanticized notions about a concept so esoteric as space travel would eventually be distorted and/or revealed for what they really are. Spaceman not only illustrates some of the pitfalls, but imagines how contemporary society might infiltrate and exploit the exploration of, ostensibly, the only remaining virgin frontier in the known universe. Our vision of space travel is first tainted by the opening scene, in which astronaut Molly Jennis (a strangely authentic and naturalistic Erin Treadway), who’s on a nine month voyage to Mars, awakens with a miserable headache (a daily occurrence, it seems), brought on by insufficient levels of oxygen in the space capsule. Who can’t relate? We’ve all woken up in a room with poor circulation and a clanky radiator spewing what must be toxic gasses. The ensuing dehydration discomfort lasts the remainder of the day. So, when we see Molly suffering through that same misery we are immediately empathetic: maybe space travel isn’t so glamorous after all. And then it gets worse.

Erin Treadway

On the exploitation side, Molly’s space suit (ingenious costume design by Heather Carey)—not initially dissimilar from those noble, pristine white uniforms that once graced heroes like Alan Shepherd, John Glenn and Neil Armstrong—is peppered with logos of corporate giants like Coca Cola, Amazon, and Google, rendering her more NASCAR than NASA. But here’s the kicker: that glamorous (and commodified) space suit also really, really stinks. Because of course it would. She’s been in the capsule unable to shower and left with only baby wipes to give herself a “bath” for months and months. And, naturally, she can’t wash the suit. Every odor that has escaped her body remains in the capule with her. And while sometimes we revel in our own scent, like a dog rolling in mud, most of us don’t like all of our own smells.

So, those are the tangible drawbacks. And even though Molly went through a battery of psychological tests to assess her readiness and ability to sustain this level of emotional isolation and mental stress, she eventually starts to seriously lose it. Perhaps it was when she received word her beloved Houston Texans football team finally won the Super Bowl for the first time in franchise history, which she missed; or perhaps when she finally had enough of hearing about the socio-political debate surrounding the public taxes being used to pay for the voyage; or the fact that her history-making expedition was basically being turned into a reality show . . . because of course it would.

Erin Treadway

We watch as Molly’s mission deteriorates—both physically and psychologically—through a series of minor mishaps, some avoidable and some not, with shades of the 2013 Academy Award winning Alfonso Cuarón film, Gravity. What’s revealed, as we hear Molly speaking with her NASA contact, Rob, as well as being interviewed by news outlets or even game shows from around the globe, is that space travel is as banal as any other activity. Though it should be the epitome of humanity’s conflict with existential philosophies, it turns out to be just another job being performed by yet another moderately damaged human who’s not much different than you or me. The tragedy is that Molly—who lost her husband Harry while he was on a prior mission to Mars—is facing this monumental and isolating event on her own. As Elton John sang, “Mars ain’t the kind of place to raise your kids./In fact it’s cold as hell.” (“Rocket Man”).

Spaceman works so well not just as a result of its introspective writing (Leegrid Stevens) and top-notch direction (Jacob Titus), but because of the brilliantly self-aware and not-overly-spiffy production design. The intricately designed and lit spacecraft doesn’t look like some gorgeous 2001: A Space Odyssey set, but rather like a vehicle designed to take a person millions of miles from earth. The combined efforts of Simon Cleveland (lighting design), Leegrid Stevens (sound design), Carolyn Mraz (set design), Jonathan Taylor (movement director), and Shawn J. Davis (puppeteer) create a realistic, yet cleverly designed setting with which an ordinary citizen can identify. We can picture ourselves making this trip, and we quickly come to realize just how utterly horrifying, in the most ordinary possible way, a trip to Mars might be. Space creatures with sharp teeth not required.

Spaceman. Through March 9 at The Wild Project (195 East 3rd Street between Avenues A & B). 100 minutes, no intermission. www.loadingdocktheatre.org

Photos: Russ Rowland