(foreground LtoR) Ismenia Mendes and Quincy Tyler Bernstine. (Background) Karen Kandel

by Carol Rocamora

It’s a wild ride, so fasten your seat belts.

Marys Seacole, now playing at Lincoln Center’s tiny Claire Tow Theater, will alternately shock you, bewilder you, infuriate you, amaze you . . . and leave you with a huge helping of food for thought.

Apparently, that’s exactly what Jackie Sibblies Drury wants. This is a playwright of fierce passion and determination. She knows how to grab an audience’s attention and keep it—as we know from her play Fairview last summer at Soho Rep, about how white audiences view race.

This time, she’s chosen to tell the exotic life story of Mary Seacole (1805-1881), a Jamaican-born healer whose adventures led her around the world. Born of a Creole mother and Scottish father, she traveled throughout the Caribbean and Central America, then on to England where she hoped to join Florence Nightingale to care for British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War. When her application was rejected, she went to Crimea herself, opened a hotel and sold provisions to British soldiers. Her widely publicized efforts captured the attention of Victorian England. She was voted “Greatest Black Briton” in 2004.

Ismenia Mendes, Quincy Tyler Bernstine, Karen Kandel, Lucy Taylor. (foreground) Gabby Beans and Marceline Hugot

What a life—and what a dazzling dramatic structure Drury has fashioned to depict it! Not satisfied with offering a straightforward chronological narrative, Drury creates several “Marys” (hence the title)—the original 19th century one as well as several in the 21st century—and time-travels from one to the other with breakneck speed. Sounds confusing? It is, at first, until you get into the rhythm of it, and then it’s mesmerizing.

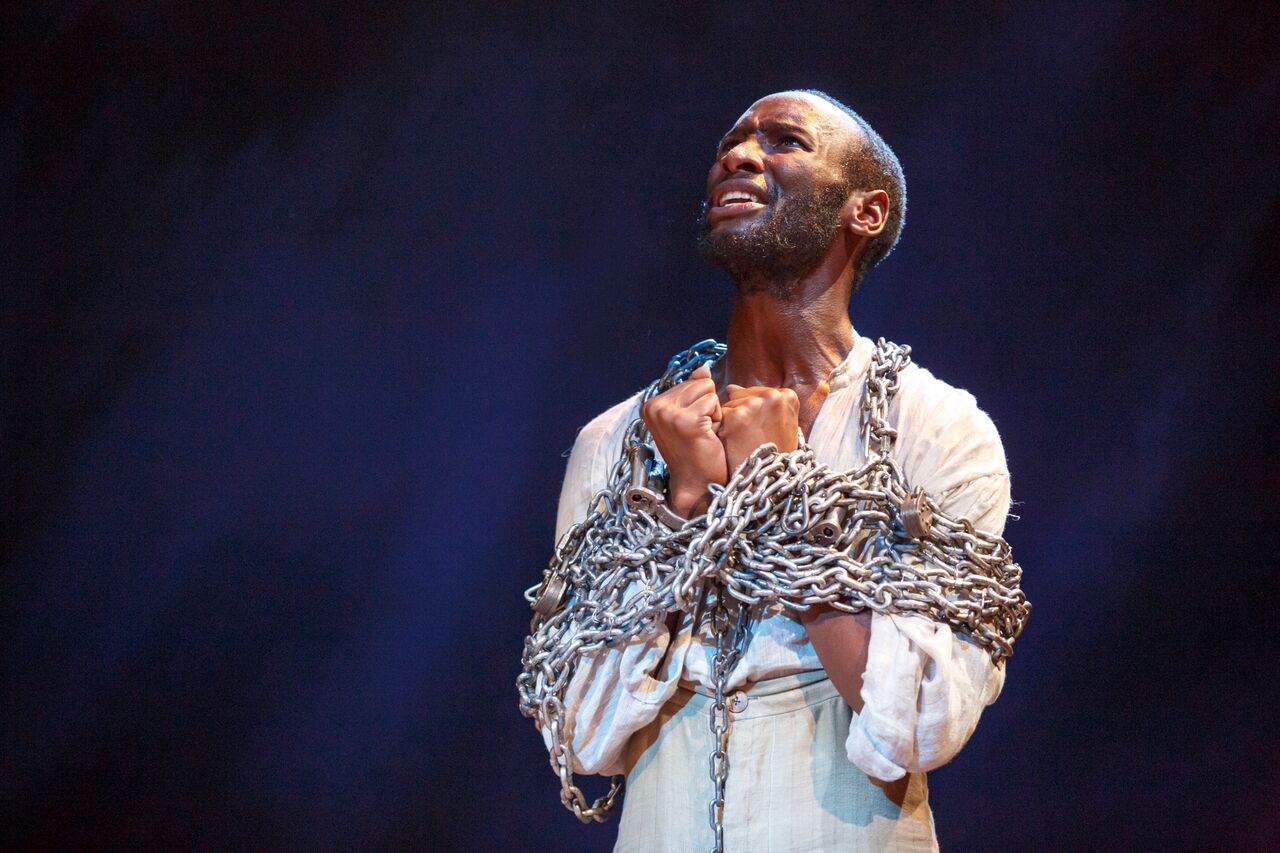

The play begins with the 19th century Mary in Victorian dress (Quincy Tyler Bernstine) telling us about her life. Enter an older woman (Karen Kandel) clad in black, who slips a Bluetooth earpiece into Mary’s ear—and presto, she’s in the 21st century, playing a hospital nurse dressed in scrubs. And so it goes, as scenes segue from the modern hospital back to the 19th century, forward again to a playground where modern Mary is minding a white child, then back again to the Crimean battlefield where original Mary cares for the wounded soldiers, and so on.

These scenes are enacted by a superb ensemble of six actresses, including others playing multiple roles (Gabby Beans, Marceline Hugot, Ismenia Mendes, Lucy Taylor). The mysterious older woman, for example, turns out to be Mary’s mother; the dying woman in the modern hospital is also the cruel white surrogate who raised Mary, etc. (The set is by Mariana Sanchez; the fabulous costumes requiring split-second changes are by Kaye Voyce.)

Marceline Hugot, Ismenia Mendes

Under Lileana Blain-Cruz’s sensational direction, the action builds to a crescendo at which the centuries and characters blur. In the frenzied, fabulous scene on the Crimean battlefield, characters race back and forth across the stage wearing costume elements from both time zones, while bodies drop spectacularly from the sky (creations of Rachel Kenner and the props team). My favorite combo is worn by Florence Nightingale, who ends up in a long black Victorian nurse’s garb, pink sneakers, and a pink backpack. Similarly, eclectic musical choices include Harry Belafonte’s “Day-O” and Whitney Houston’s “I’m Every Woman.”

Why has Drury chosen this radical mode of story-telling, you might ask? To capture our attention, evidently. Like Caryl Churchill, Drury shocks us with unconventional dramatic form. Like Sarah Kane, Drury shocks us with content. Drury’s message is urgent, and she uses extreme means to convey it. “I’m the most impressive woman you have ever encountered!” Mary exclaims at the play’s conclusion. Clearly, Drury is saying that women of color still need to prove themselves and justify their accomplishments, because who else will? “Me give power to myself!” Mary declares, triumphantly.

Drury may go too far, by some theatrical standards. The question is: Do the ends justify the means? See for yourself.

Marys Seacole. Through April 7 at Lincoln Center’s Claire Tow Theater (150 West 65th Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). 100 minutes, no intermission. www.lct.org/shows/marys-seacole

Photos: Julieta Cervantes