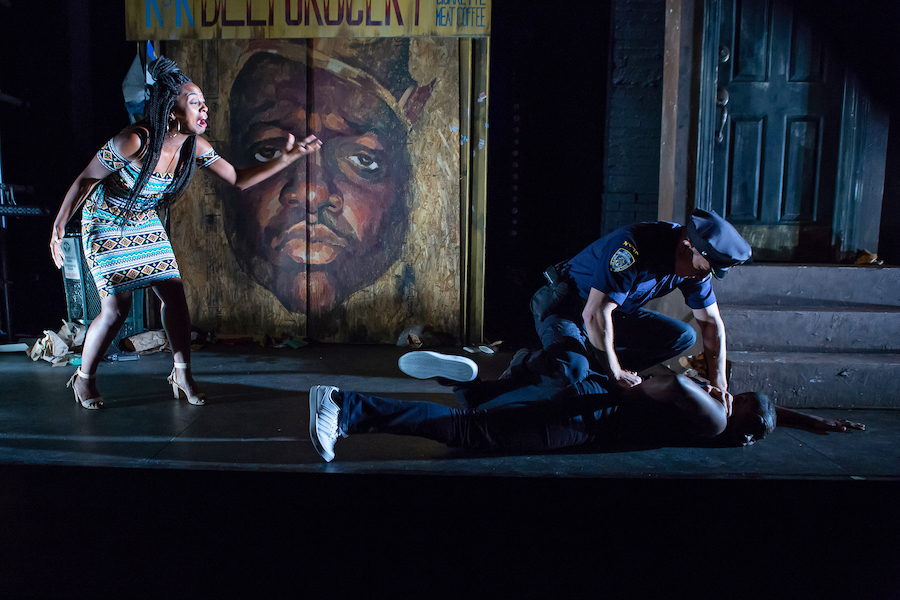

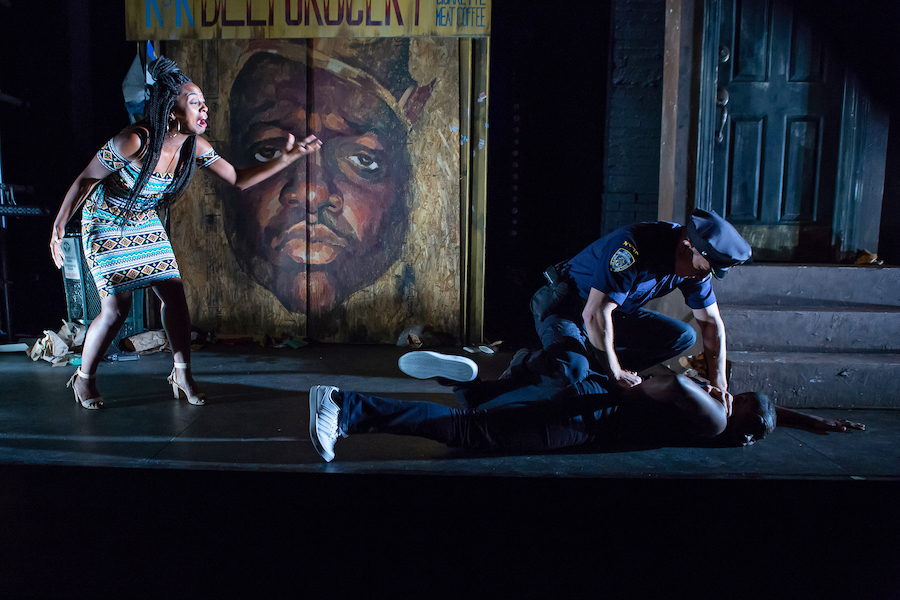

Alana Raquel Bower (left), Andrew Baldwin (top right) and Michael Oloyede (bottom right)

by Samuel L. Leiter

Scraps is an angry play. Not that it doesn’t have plenty to be angry about. However, the solution it takes to dealing with its issues suggests a course in anger management may be in order.

Written by Geraldine Inoa, the inaugural recipient of the Shonda Rhimes Unsung Voices Playwriting Commission, Scraps kicks off the Flea’s 2018-2019 “Color Brave” season in which race is the overarching theme. As artistic director Niegel Smith says, “In today’s climate the subject of race and color afflicts and then divides us all.”

Inoa wants to dramatize how the killing by a white cop of an unarmed black man in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, on the Memorial Day weekend of 2014, affects those he left behind. She gives only the barest details; it was the middle of the night, he was wearing a hoodie, he was running. Since so few facts are offered, the assumption is that he was innocent and that, in racist America, even innocent blacks should never run from the “pigs.”

Midway through, when we witness the ruthlessness of another white cop (Andrew Baldwin), we see that Inoa has more on her mind than expressing the agonies endured in the wake of a loved one’s unjust death. This is when Scraps becomes anti-police, anti-white agitprop. Many liberal whites, if they feel guilty enough, will respond with applause. It’s not likely, though, that the folks next door, home of the New York State Police, will be buying lots of tickets.

Tanyamaria, Roland Lane

The play begins with an expository rap poem introducing us to these “blood-stained streets.” It’s performed by a disheveled, weed-smoking Haitian-American rapper, Jean-Baptiste Delacroix (Roland Lane), who sits on a stoop fronting a dilapidated building. (Set by Ao Li.) At one side, a grocery’s iron gate is painted with the glowering face of the late Notorious B.I.G., whose hip-hop numbers form much of Megan Deets Culley’s soundscape.

Forest Winthrop, the victim, was a respected young man with a potential future in the NFL, a career that would have made him “the richest nigga to come out of here since Jay Z.” His bereaved friends are Jean-Baptiste, 20, the rapper; Forest’s girlfriend, Aisha Douglas (Alana Raquel Bowers), 23; her sister, Adriana (Tanyamaria), 22; another friend, Calvin Young (Michael Oloyede), 19. Then there’s Forest’s little boy by Aisha, Sebastian.

In Act I, three months after the killing, on the Labor Day weekend, we meet all but Sebastian. Jean-Baptiste is an out-of-work slacker who believes getting a job should be secondary to his dream of rapper stardom; Aisha is worn out from working so hard to put food on the table and raise Sebastian; Adriana, an NYU student who says she hates white people, suffers from anxiety; and Calvin, a Columbia undergrad, is visiting after spending the summer in London, from which he’s returned in cap, tweed, tie, and vest. (Costumes are by Andy Jean.)

Forest’s friends, their grief and despair still raw, grumble and argue loudly about work, race, injustice, entitlements, relationships, sex, fidelity, education, and so on. Sometimes they rap and dance, behavior that segues into an act-ending scene of inhumane police violence, staged by Michael G. Chin.

Each character uses vulgar language in which every sentence seems to contain the “n-word.” Occasional implausibilities arise, as when Inoa wants to show, despite their crudity, how educated her people are. Okay. But James Joyce? Under Niegel Smith’s direction, the Flea’s resident company, the Bats, struggles to make this material more than skin-deep or, in a couple of cases, to consistently speak the machine gun-paced dialogue so that every word registers.

Roland Lane (top left), Tanyamaria (bottom left), Bryn Carter (center), Michael Oloyede (top right), and Alana Raquel Bowers (bottom right)

Act II of the intermissionless play jumps ahead three years. Following another horrific death, which we witness to the voice of Nina Simone singing “Strange Fruit,” the scene becomes an expressionistic funeral centered on the presumably post-traumatic suffering of now eight-year-old Sebastian, dressed in black suit and red tie and played by an adult actress (Bryn Carter).

As the nightmare funeral morphs into a bizarre game show, with everyone dressed similarly, the ensemble—coming together with superb vocal and physical cohesion—behaves in surrealistically rhythmic fits and starts, complemented by Kate McGee’s phantasmagoric lighting. In its midst, Carter delivers a riveting performance as the anguished child.

When it ends, Scraps—whose title refers to the leftovers American blacks used to survive—reiterates, in no uncertain terms, its furious message about teaching the cops a lesson. Without excusing the well-documented swath of police brutality toward blacks, it’s nonetheless necessary to note that, as expressed in Scrap’s simplistic shorthand, such a message may not offer the best solution for healing a problem that, to repeat Smith’s words, “divides us all.”

Scraps. Through September 24 at The Flea Theater/The Siggy (20 Thomas Street, between Broadway and Church Street). www.theflea.org

Photos: Hunter Canning