Paul Alexander Nolan, Teyonah Parris

by Brian Scott Lipton

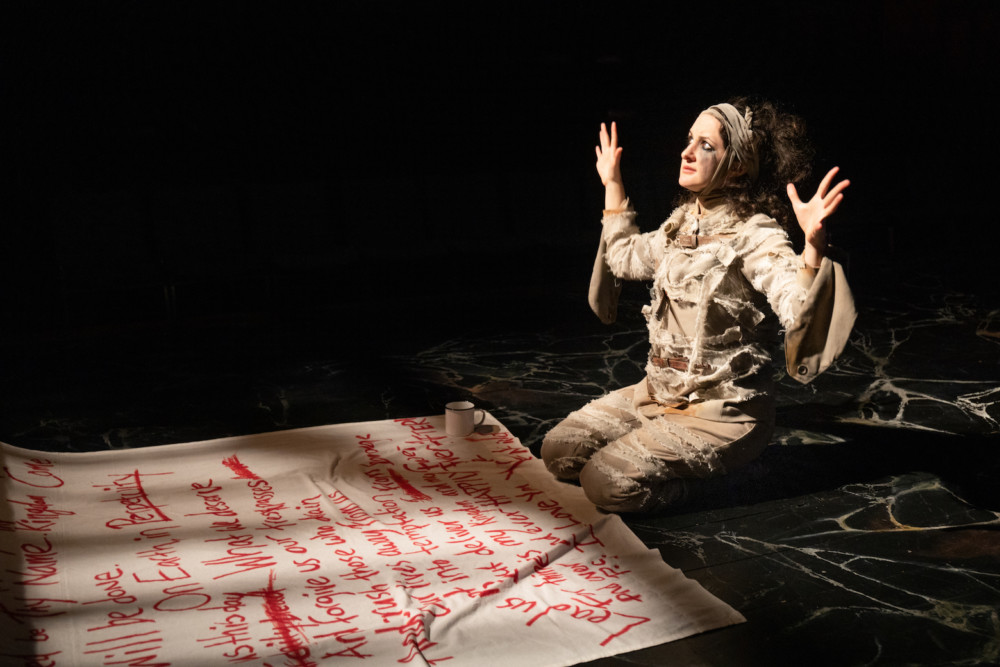

It’s hardly a secret that in the Antebellum south, white owners often took sexual advantage of their African-American slaves. But in the first 45 minutes of Jeremy O. Harris’ audacious, beautifully-acted Slave Play, now debuting at the New York Theater Workshop, we witness (in somewhat graphic detail) three variations of this phenomenon. Jim (Paul Alexander Nolan), a white overseer on a Virginia plantation, has his way with a sassy female slave, Kaneisha (Teyonah Paris); Alana (Annie McNamara), the frustrated white wife of a plantation owner, uses a sex toy to penetrate the bare ass of her strapping male servant, Phillp (Sullivan Jones); and Gary, an African-American slave (Ato Blankson-Wood) and Dustin (James Cuasti-Moyer), a white male indentured servant, indulge in some hot-and-heavy fetishized sex. To quote the ever-popular rock group Queen: Is this the real life or is this the fantasy?

The answer to that question isn’t really in doubt, thanks to Harris and the brilliant direction of his collaborator, the equally provocative Robert O’Hara (Bootycandy, Barbecue). Clues abound almost instantly, from the popular music (notably Rihanna’s “Work”) that provides the soundtrack to some of these encounters to the spiky plastic boots worn by Alana to the unexpected use of the word “Starbucks” at a pivotal moment. But what exactly we’ve been watching isn’t something even the savviest audience is likely to figure out quickly, and if you want the rest of “Slave Play” to remain a mystery, just stop reading now.

Annie McNamara

The aforementioned sextet are actually three modern-day interracial couples who have agreed to participate in a study of “Antebellum Sexual Performance Therapy,” a fairly radical experiment that’s been concocted by an interracial lesbian couple, Tea (Chalia LaTour) and Patricia (Irene Sofia Lucio), who can’t stop babbling in “theraspeak” and bragging about their time at Yale. Their intent, alternately noble and misguided, is to allow African-American who feel sexually frustrated in their relationships to regain some measure of control as well as express their feelings openly. It works—on its own merits and theatrically—but only up to a point.

Indeed, the show’s hour-long second section is devoted to exploring the couple’s dilemmas (which may feel familiar to anyone involved in a long marriage or partnership), as well as a hearty dialogue about identity, racial and otherwise, in today’s America. Phillip, the most light-skinned of the three, claims he doesn’t really feel “black,” until the session triggers a painful memory from his college days. Gary beautifully expresses his sense of being the undervalued partner in a society where African-Americans are almost immediately considered second-class citizens, especially as his feelings are exacerbated by the fact that Dustin is a needy, vain actor who also insists he’s not really “white.”

Sullivan Jones, Annie McNamara

And Kaniesha says little, until she explodes after Jim tries to “explain” himself via a text he wrote in the restroom, which, ironically, pinpoints the largest issue at hand. “When your people landed on this land, a third of the indigenous population of the entire continent died of disease. Not disease you actively gave them. Your mere presence was biological warfare. You are a virus. The virus,” she notes.

Much of the couple’s interchanges are fascinating, but I wish they were a little less repetitious (at over two hours without intermission, the play is a longish sit), and Harris hardly needed to stack the deck by also giving each of his African-American characters a weird form of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

James Cusati Moyer, Ato Blankson Wood

Still, it’s the final section of the play, as Kaneisha and Jim make one last attempt to reconnect in their hotel room (which makes optimum use of Clint Ramos’ mirrored set), that might be Harris’ finest achievement dramatically. Having found her voice, Kaneisha is no longer afraid to use it—including sharing a telling story about being the only African-American schoolgirl on field trips to Virginia plantations—while Jim, utterly clueless, still somehow believes she prefers to be silenced.

As they say, those who don’t learn history are doomed to repeat it.

Slave Play. Through Sunday, January 13, 2019 at New York Theatre Workshop (79 East 4th Street, between Second Avenue and The Bowery). Two hours, no intermission. www.nytw.org

Photos: Joan Marcus