by Michael Bracken

To say that Man from Nebraska, at Second Stage’s Tony Kiser Theatre, starts slow is nothing if not an understatement. Ken (Tony Award winner Reed Birney) and Nancy (Annette O’Toole), a fifty-something couple living outside Lincoln, go from car to church to cafeteria, barely saying a word to each other, at a speed that’s way under the limit.

Playwright Tracy Letts (August: Osage County) makes it crystal clear these are unexceptional people leading uneventful lives. Routine reigns. They don’t talk unless they have something to say. They’re capable of small talk, as they show when they visit Ken’s aging mother, Cammie (Kathleen Peirce), in a nursing home. But with each other, silence is fine.

Cammie, played with uncompromising candor by Peirce, livens things up a bit. While she still has some of her wits about her, her memory is diminished and her worldview has shrunk. She’s focused on meeting her basic needs. And she’s hungry. So, once she learns Ken and Nancy have brought food with them, she’s relentless with the refrain, “Gimme some ham.”

The play really shifts into gear when we see Ken in the bathroom, in the middle of the night, shaking, crying, sobbing, determined to keep Nancy at bay as she calls to him from their bed. Nancy joins him in the bathroom despite his protests, questioning him and tossing out possible culprits in rapid succession. Heart attack? Stroke? Nightmare? Pain? Sick? No, or no answer, to all of the above.

Finally, he gets to a point where he can explain the source of his distress. “I don’t believe in God.”

Birney, excellent throughout, is especially affecting here. He allows us to see the entire torrent of emotions that flood over and just about drown Ken. Pain, confusion, bewilderment, guilt – even terror – they’re all there, and Ken doesn’t know what to do with them. He’s completely at sea.

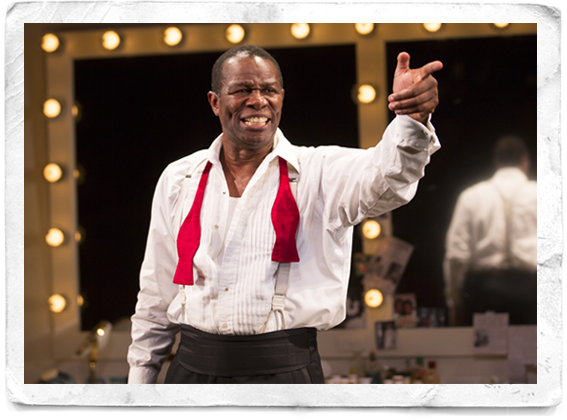

His pastor suggests a vacation, and soon Ken is on a jet to London, where he meets and befriends Tamyra (Nana Mensah) and her artist boyfriend, Harry (Max Gordon Moore), who teaches Ken to sculpt.

Meanwhile, Nancy is back in Nebraska, dealing with her daughter Ashley (Annika Boras), who is enraged at her father, thinking he has abandoned her mother. Nancy plays Penelope to Ken’s Odysseus, fending off the advances of Bud (Tom Bloom), who wants to make time in Ken’s absence. O’Toole is barely noticeable but exudes a soft glow and a strong moral core. Her Nancy is steadfast and quiet but capable of standing up for herself when she needs to, as when Bud crosses over the line.

One of the striking things about Letts’s drama is the way it sneaks up on you. Its sedate beginning gives way to a pace that slowly gains ground almost without our noticing. Intermission seems to come too soon. The second act beckons because of the unobtrusive skill with which the first act has laid its groundwork.

David Cromer’s direction is of a piece with Letts’s writing, simple and clear. The play’s progression is seamless. Except for Ken and Nancy’s bedroom, Takeshi Kata’s sets are minimal, a piece or two of furniture, precisely lit by Keith Parham. No one element of this production clamors for attention, allowing us to take in the humanity that pervades the entire piece.

First produced in Chicago in 2003, Man from Nebraska is an intimate drama that examines a good man trying to wend his way through a crisis of faith. While Ken sees it as revolving around his faith in God, it’s as much about his faith in himself, his faith in anything. It seems simple because it’s so basic, but it’s not really very simple at all.

Man From Nebraska. Through March 26, at the Tony Kiser Theatre (305 West 43rd Street at 8th Avenue). Two hours 5 minutes with one intermission. www.2st.com

Photos: Joan Marcus