by Michael Bracken

Almost thirty years since it first fluttered onto the stage, M. Butterfly is back on Broadway, in a stunning production directed by Julie Taymor. Playwright David Henry Hwang has made some minor revisions, but the play still packs the dramatic wallop it did in 1988, when it won the Tony Award for Best Play.

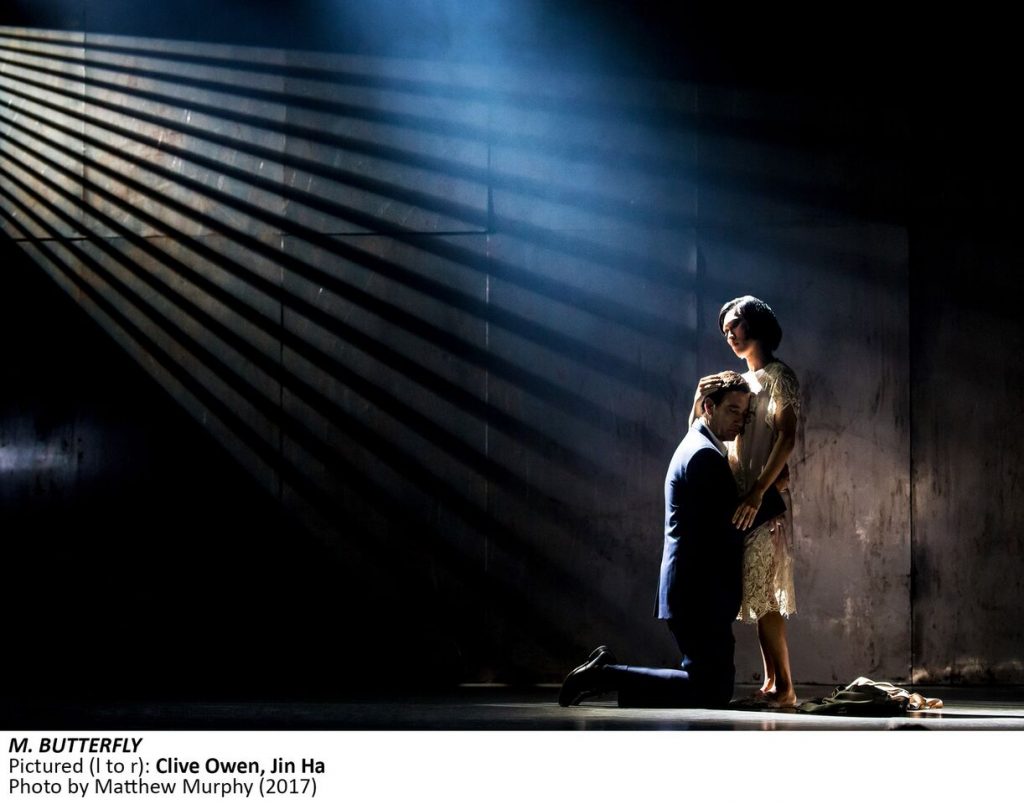

Loosely based on a true story, Butterfly spans twenty-odd years as French diplomat Rene Gallimard (Clive Owen) looks back from his Parisian prison cell in 1986 to the time he was stationed in China. His memories are dominated by his affair with Peking Opera star Song Liling (Jin Ha), also known as Butterfly. He’s on trial for treason, because he shared classified information with her, which she in turn shared with the Chinese. Until his arrest, he never realized that his China doll of a mistress was, in fact, a man.

References to Puccini’s Madame Butterfly, in which an American soldier impregnates and abandons his Japanese mistress, abound. Song points out the racism inherent in the opera’s appeal: strapping white man conquers submissive Asian girl, who kills herself when he leaves her, while he goes back to his newfound American wife. The drama’s ending reflects, in a funhouse mirror distortion, that of the Italian opera.

Hats off to Taymor, who peppers the play with vivid pageantry bursting with color, as when the Peking Opera flashes across the stage in a vibrant exhibition of gymnastic prowess. Constance Hoffman gets credit for costumes, Ma Cong for choreography. Taymor takes the spectacle of the Chinese opera troupe’s performance, splendidly choreographed, and lets it reveal both its beauty and its foreignness. In that way it’s not unlike Butterfly.

Paul Steinberg’s scenic design is efficient and ingenious. The stage is often bare, except for six large banner- like panels that create all sorts of settings. Sometimes they simply function as walls. At other times they have images on them and splashes of color. When the proletariat is in a frenzy of Maoist fervor, each screen has the same image of Mao on one side and different Chinese symbols on the other.

Yet Taymor’s sense of spectacle never gets in the way of what, if rocky and ultimately tragic, is a tender love story. Gallimard and Butterfly’s intimacy, for what it is, remains center-stage.

Early on, Gallimard tells us that he was voted, in grammar school, the boy least likely to be invited to a party. And that’s who Owen becomes. Even when he’s being cruel – as when Gallimard keeps Butterfly hanging, early in their courtship – he’s the little boy who didn’t get chosen for the team. He’s not exactly a loser, more of an also-ran. Gallimard’s humbling notoriety for not knowing the true sex of his mistress doesn’t completely humble him. With half-mock bravado, he relishes his celebrity, and Owen captures the contradiction, the cynicism, the sincerity.

Hwang has Gallimard talk to the audience a lot, so we get to know him well, and we’re on his side, rooting for him. He’s opportunistic, not so much as to be off-putting, but enough to be wary of. When he’s cheating on his wife by having his affair with Butterfly, another woman pops up, and he has a fling with her too, drunk with his sexual power. Owen manages to bring this complex photo into focus, and he does so with an extremely light touch.

Jin Ha is a wonderful Song. Petite and demure, he doesn’t hide the machete beneath the makeup as he plays Gallimard like a French horn. We accept him for the woman he is and isn’t.

Butterfly is an enthralling play that’s lost none of its luster over time. Taymor, Owen, and Ha make major contributions to this exciting production, but it’s Hwang’s tight, toned and fluid script that is the star.

Photos: Matthew Murphy

Open-ended run at the Cort Theatre (138 W. 48th Street). www.mbutterflybroadway.com. 2 hours 20 minutes with one intermission.