by Susan Hasho

Occupied Territories is a memory play strung together with grit and realism. Two daughters have gathered in their father’s house after his funeral. Jude has been let out of rehab to attend, her sister Helena has been taking care of her daughter Alex and we find the three of them in their father’s basement looking through his stuff. He is a Vietnam vet with enough damage to have hurt the entire family. They are discussing the father’s instructions for the sale of the house and in the distance we hear soldiers singing a marching song. Slowly the soldiers march through the back of the audience and assemble onstage. We are then simultaneously in Vietnam and in the vet’s basement at home.

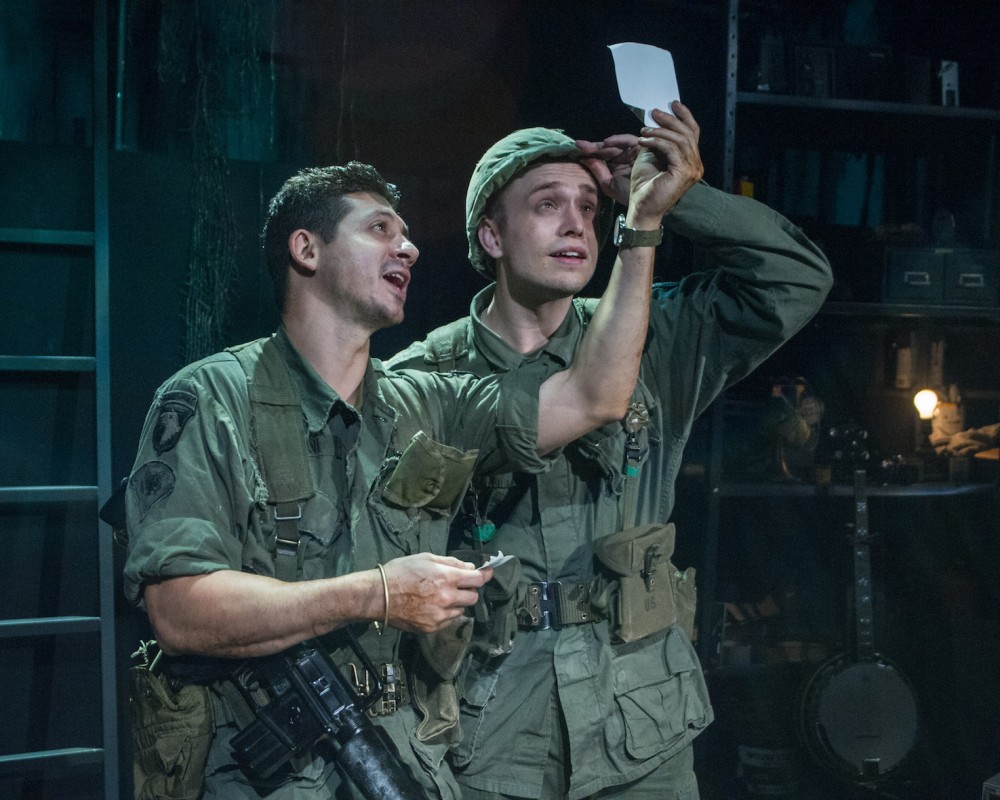

The soldiers are in 1967 Vietnam carrying out a routine mission, calling in for new supplies and passing the time with jokes, harassment of a new soldier and ongoing surveillance of the site. It is clear that Collins is new to the team and that he is not yet trusted. As the play goes on it also becomes clear that Collins is the father of Jude and Helena. We switch back and forth between basement and battlefield learning the details of each woman’s relationship with their father and the resentments they have against each other. Jude doesn’t want to forgive her father; Helena would rather move on and create a rosy life. And in the jungle, Alvarez shoots a Vietnamese woman thinking her a soldier. Battling remorse, all the soldiers react in different ways. But it is articulately clear that these men are ill equipped for this war. The only way they can get through it is to forge deep loyalty and love for each other. Collins’ handy camera always in tow, he is asked to take pictures of the dead Vietnamese woman in various poses.

Jude in her father’s basement finds the pictures, and also a carousel of his slides. Soldiers hold up a screen and we see Collins’ pictures on the screen. We are seeing the war and the daughter experiencing the war through pictures at the same time. It is a very clever device to use Jude experiencing what her father went through by looking at pictures and video, and the father living through it at the same time. As the slides continue, two soldiers move powerfully through choreographed movement that illustrates their closeness and interdependence. This graceful, complicated dance shows the wide gamut of feelings all these men have to navigate through in order to deal with their extraordinary situation.

At the same time, Jude is struggling with the pills she has found in one of her father’s boxes. She is grappling with the reality of her father’s situation through his eyes. She takes the pills. On the battlefield the soldiers are running out of supplies and need to move to where a supply helicopter is expected some miles away. They set up a patrol, leave two behind and move on.

At the same time Jude realizes that the pills are destroying her hope of being with her daughter Alex, the band of soldiers waiting for the helicopter are attacked. All die except for Collins.

Jude realizes her flaws are very like her father’s. He hid in the basement and she hid in addiction.

The play ends in a circle: soldier to soldier, daughter to daughter. All are hurt. All are inextricably part of the same tragic war—simultaneously and yet years apart.

The director Mollye Maxner achieves a difficult task and makes each location distinct and yet each flows into the other. The focal points are always clear and alive, and the actors always distinctly in their own worlds. As playwrights Nancy Bannon and Mollye Maxner have provided a very clear canvas to fill. And the actors live in their allotted worlds with great emotional reality and passion. The three women Nancy Bannon as Jade, Ciela Elliot as Alex and Kelley Rae O’Donnell as Helena rotate around each other carefully, set in motion by Collins’ death and their own good actor instincts. Ace, as played by Donte Bonner, is a man of integrity and tightly held anger. He holds this squad together in spite of great fear and danger. Collins (Cody Robinson) creates a highly detailed journey from shy cornpone to survivor. We really only fully see his face at the end of the play when he allows himself to be revealed. His is a quietly subtle performance. Scott Thomas as Ski walks a dangerous tightrope with skill and angry grace, and he commands attention. Nile Harris as Hawk and Thony Mena as Alverez are physically deft and in total control of the emotional journey they are making. The entire cast works together as a beautiful ensemble. This play ends in a circle that includes the audience because we were invited in from the beginning—we just didn’t know it until the end. Bravo.

Performances are at 59E59 Theaters (59 East 59th Street, between Park and Madison Avenues). Single tickets are $25 ($17.50 for 59E59 Members). To purchase tickets, call Ticket Central at (212) 279-4200 or go to www.59e59.org