by Michael Bracken

It might take you a while to figure out what playwright Steven Levenson is up to in his Days of Rage at the Tony Kiser Theater. Presented by 2nd Stage, Levenson’s murky comedy turns out to be a satire of the sixties, but that’s not initially clear. His jibes at the counterculture are too few and too faint. Eventually they gain traction but it’s too little, too late.

A satire should announce itself loud and clear, right out of the box. Levenson’s first scene hints at the play’s whereabouts but not its tone. Jenny (Lauren Patten) hands out leaflets in front of Sears, where Hal (J. Alphonse Nicholson), a Sears employee, reluctantly tells her she has to move on. Not much satire there.

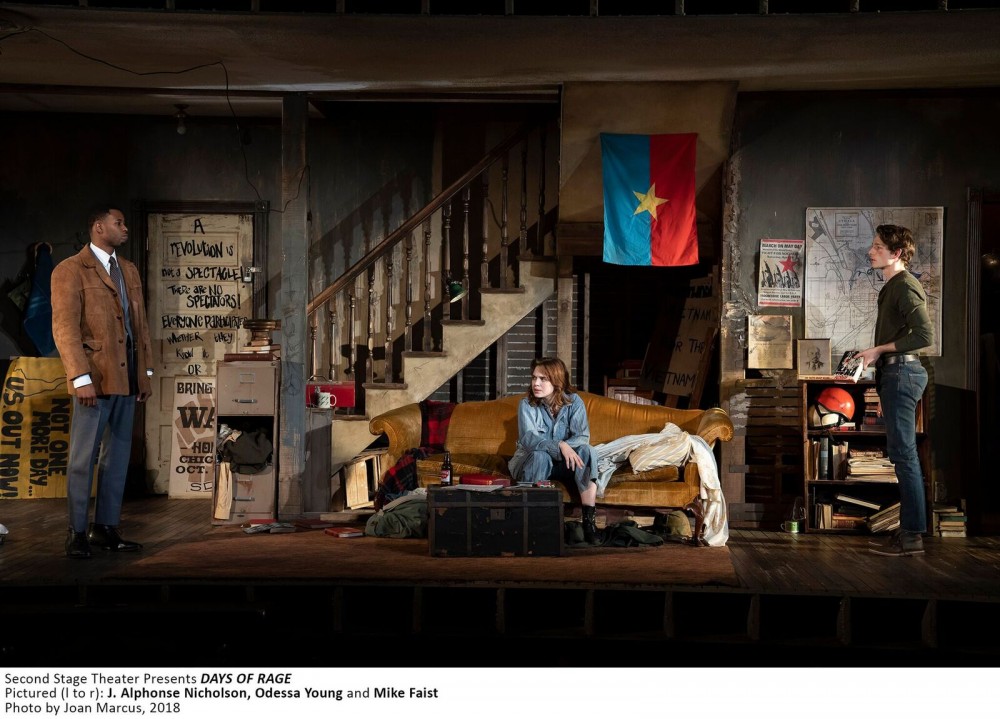

The irony is more pronounced that evening at Jenny’s home, which she shares with Spence (Mike Faist) and Quinn (Odessa Young). They are a collective of three, avidly embracing form over substance as they turn a simple conversation into a parliamentary debate, followed by a unanimous vote. Yes, Jenny should call her parents to ask for money because the members of the collective are collectively broke.

It’s scenes like this that give Days of Rage what fire it has. A collective of three is a ridiculous concept and the scene is laced with humor. But the trio is a little too close to home to jump start the comedy. They’re self-important jargon-spouting disciples of the revolution-in-waiting, not far removed from real prototypes.

Jenny is the most rational, least radicalized of the group. In Patten’s hands she’s likable, committed to the movement but starting to question its tactics. Her ambivalence is exacerbated by her budding relationship with Hal, the Sears employee who tracked her down after giving her the boot.

Quinn is the most hard-core. Completely committed to the movement, she all business, never cracking a smile. She resents Jenny for being Spence’s former girlfriend. Although they’re supposed to be above individual attachments, she carries a torch for him.

Spence is somewhere in the middle, closer to Quinn’s unquestioning determination but without the bitterness. He’s protective of Jenny, easily manipulated by Quinn.

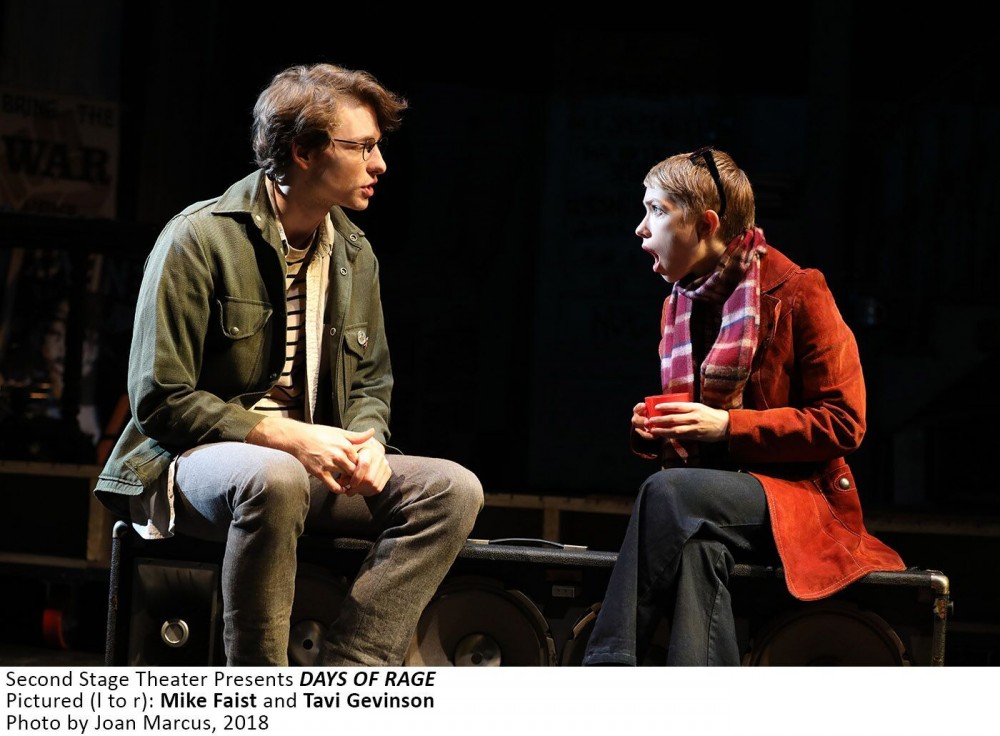

And then there’s Peggy (Tavi Gevinson), who appears from out of the blue and talks her way (with the help of two thousand dollars in her backpack) into the house and eventually the collective. With shrill persistence, Gevinson’s Peggy is a mosquito that won’t go away. She stokes the flames of Quinn’s dislike of Jenny and commandeers the collective, calling for Jenny’s expulsion for lacking doctrinal orthodoxy. She’s funny in a very strident way.

So the characters drolly disdain bourgeois individualism and bemoan the end of the white working class, whose historical mission is over. The problem is they’re not much larger than life, which they need to be if a play like this is going to crackle.

A director is limited by the material he or she is given but sometimes can transcend it by directing outside the box. That doesn’t happen here. The only notable mark of Trip Cullman’s direction is how his actors scurry around the set with exaggerated urgency between scenes. It’s affected but not sardonic. More pronounced visuals might have helped Days of Rage find itself onstage.

Sex, always a crowd-pleaser, is the one area where the play breaks out with a flourish. Monogamy, we learn, is another form of slavery. Many scenes end with coitus breaths away. As Quinn puts it, they share everything else, why not their bodies?

At one point, Jenny tells Peggy about two collective members who left the group because it wasn’t disciplined enough. When they were around, there was a calendar of who was supposed to sleep with who when. That’s the kind of detail Days of Rage could use more of.

Through November 25th at Second Stage’s Tony Kiser Theater (305 W 43rd Street). https://2st.com/shows/current-production/days-of-rage . 90 minutes with no intermission.