by: JK Clarke

Scratch the surface of Bedlam Theater Company’s productions of Hamlet and Saint Joan (now playing in repertory at the Lynn Redgrave Theatre) and you’ll find four of the hardest working actors in New York, if not the world. Go a little bit deeper, and you’ll find two truly remarkable and entertaining performances of two of the more nuanced and complex plays ever written. And all with just four actors. In a season that has seen a surge in repertory productions of classical plays (Globe’s Twelfth Night/Richard III at the Belasco, as well as Waiting for Godot/No Man’s Land at the Cort), these two productions are noteworthy standouts.

What Bedlam has done is stripped these great plays down to their essentials. In both, there are costume changes, though there are few real “costumes” to speak of. The characters wear contemporary street clothes, or perhaps business or clerical attire to help identify social position. The vestments that matter most are practically props: a pair of glasses or a hat signify change when one actor is playing several characters in a scene. As for the set, it is essentially the theater itself. The company uses every nook and cranny, sometimes sitting next to and addressing audience members, sometimes climbing over chairs, sometimes shouting from the sound booth. And in both, the seats drastically rearranged at intermission.

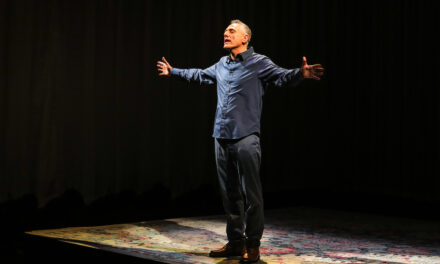

The cast of Hamlet is already large, but each character has several different personae: Ophelia goes through dramatic shifts in personality and mood; the king’s advisor, Polonius, is at times a doting father, a noble counselor, and Claudius’s co-conspirator; Queen Gertrude is a loving mother, adulterer and “grieving” widow; and Claudius himself is a man of many faces. Then there’s the already convoluted play-within-a-play Hamlet orchestrates, wherein he “catch[es] the conscience of the King.” Yet somehow, the company makes these characters and personalities abundantly clear. Eric Tucker (who also directs both plays), is Hamlet and several other characters. He is snide, suspecting, cynical and above all enraged. We feel him through every one of his twists and turns. He conspires, asks for our sympathies and chuckles along with us in disbelief of the audacity of those conspiring against him. He is our friend, and ultimately we are sad to see him go. Andrus Nichols is a painfully maligned, disturbed and meandering Ophelia; she is also Gertrude, trying to make peace and go with the flow, hurt by her son’s refusal to allow the crimes of the court to go unpunished. Nichols, too, plays several male characters, sometimes swapping gender utterly convincingly in a single beat. She is a powerful and commanding actor whose every role is emotional and profound.

Edmund Lewis (Polonius, Horatio, et al) and Tom O’Keefe (Claudius, Rosencrantz, etc.) are simply outstanding in their innumerable roles, using different voices and a physical realignment of their bodies for each character. They would be strong players in merely their principal roles, but become so much more by playing the others. At the end of the second intermission just before the play restarts, Tucker welcomes the returning audience and says, “hang in there; we’ll all be dead in 45 minutes.” And, sure enough, all four are in a muddy scrum on the floor at the play’s end.

George Bernard Shaw’s Saint Joan, is the story of a medieval French farm girl guided into war heroics (apparently) by God, but pitted against a world which has deemed her either insane or heretical. Joan heard voices of saints and God, commanding her to lead the French army to victory against England, but betrayed and burned at the stake, then (much later) canonized for her efforts. She may have been delusional, but she had the courage of her convictions. More than anything else, Saint Joan is a meditation on the nature of divinity and authority: who has the right to say whether or not they communicate directly with God? Is it solely the dominion of the church and its authorities? Do individuals not have the right to interact with their own deity? As Joan becomes more of a perceived threat to the church she is sternly warned by the Archbishop:

“You came clothed with the virtue of humility; and because God blessed your enterprises accordingly, you have stained yourself with the sin of pride. The old Greek tragedy is rising among us. It is the chastisement of hubris.”

Sure enough, the collision of the Church’s insecurity and Joan’s audacity seal her fate. While Shaw was not entirely atheist, as a socialist he disdained central, hierarchical authority and uneven distribution of power. The idea that the church would tell one person they couldn’t communicate directly with God was surely disturbing to him. He did seem to revere Joan of Arc, however, which is a notion that would probably disturb him today, as she has come to represent the jingoistic and bigoted French nationalist political party, Le Front National.

In Saint Joan, Andrus Nichols plays only the role of Joan. Because of both the intensity of her role and the isolation of her character, Nichols’ character must be pitted against the others: soldiers, church officials, English nobility and King Charles. Tucker, Lewis and O’Keefe beautifully round out the other characters, with Tucker as the pragmatic and haughty aristocrat (with a terrific upper class accent), Lewis as the wormy Dauphin (and eventual King) and O’Keefe as the whiny Archbishop. They are clumsy and inept to the point of comical, yet effectively conspiratorial. When Joan is burned and then celebrated, they are all regretful, mostly out of fear of reprisal (from God, from the common people). But Joan is overjoyed, even beatific.

What Bedlam has done here — having four actors play over 50 roles from two plays (on separate days, of course), that clock in over three hours each, sans set or costume — is absurdly difficult and complex. Impossibly so. But, in a miracle worthy of Saint Joan herself, they pull it off not just with the (seemingly) greatest of ease, but in a stunningly powerful fashion. They prove beyond any doubt that great plays don’t require over-stuffed, fancified, expensive productions; but instead a thorough appreciation, understanding and ability to share the material with the audience. A good reading, in other words. Any and all students of theater – not to mention lovers of terrific classical theater – should go see both these plays right away. Where the Globe’s productions (previously reviewed on this site) are perfection on a grand scale, Bedlam’s Hamlet and Saint Joan are the greatest possible example of raw, primal theater. Both are immensely enjoyable and offer us the majesty and magic of the stage.

Hamlet and St. Joan. Through February 2, 2014 at the Lynn Redgrave Theater (The Culture Project, 45 Bleeker Street, between Lafayette and Mulberry). www.theatrebedlam.org or www.cultureproject.org

*Photo: Elizabeth Nichols