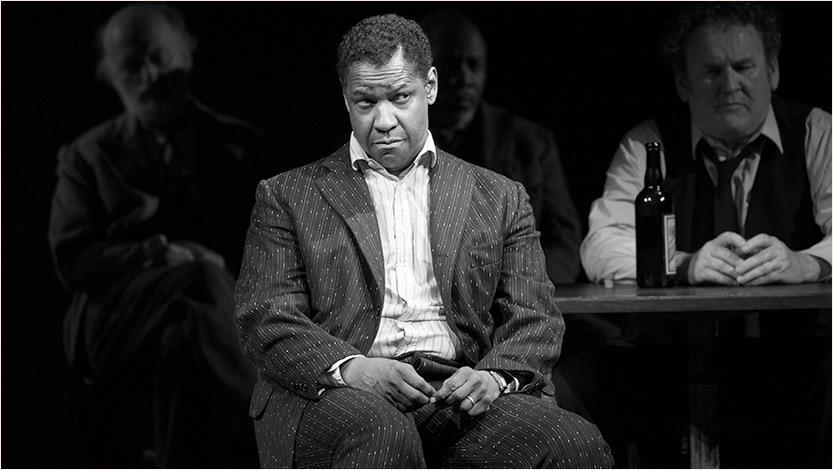

Michael Potts, Colm Meaney, Denzel Washington, Jack McGeen, Tammy Blanchard, Neal Huff, Reg Rogers, Dakin Matthews

by JK Clarke

As any health or behavior expert can tell you, the root cause of substance abuse is rarely, if ever, the substance itself. Rather, it’s the underlying mental or emotional suffering of the user that leads to it, and those issues must be addressed if the individual is ever to become healthy again. Sadly, the alcoholics who reside, day and night, in Harry Hope’s miserable Greenwich Village saloon, circa 1912, in Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, don’t know that. And neither does the man who dreams of leading them to recovery, to getting them to abandon their “pipe dreams,” by cleaning up and actually pursuing their normal lives. But, the vast majority of these folks are doomed, and really that’s the tableau O’Neill lays before us. But, hey, at least they have each other.

This revival of this O’Neill classic at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre on Broadway is the first in almost 20 years. Director George C. Wolfe opens this production with Harry Hope’s resident rummies sleeping at tables strewn across the stage like some sort of liquid Last Supper. As they rouse, shaking in anticipation of the day’s first drink, they reignite the same banter that reigned each day before: petty arguments, insults, reminiscences and excited, hopeful talk of a forthcoming birthday party for Harry. Hickey (Denzel Washington) is the only one who goes out and does real world work—as a traveling salesman—but he always returns for a soul-crushing binge. They love him because he’s a lively showman and the life of the party; but they love him even more because he buys them drinks. Hickey is the worst pipe dream of all.

David Morse, Denzel Washington, Colm Meaney

These men, plus three ladies of the night, are the indoor version of Skid Row. All once existed in the real world, had potential and still harbor hopes to return to some version of “normal” life. Among them are Larry Slade (David Morse, who wears his inner conflicts on his furrowed brow, while saying little), a former anarchist/workers party advocate; Willie Oban (Neal Huff, displaying heartbreakingly comic delirium tremens), a Harvard Law School grad never quite made it in his field largely because of anxiety and alcohol; Joe Mott (Michael Potts, so remarkably versatile that no one would ever recognize him here as the hitman Brother Mouzone in HBO’s The Wire); former circus- and con-man Ed Mosher (Bill Irwin, whose mastery of physical comedy makes this vaudevillian character all the more delightful); saloon owner Harry Hope (perfectly cast Colm Meaney); and many more.

The Godot these sots await finally shows up in the form of Theodore “Hickey” Hickman (the remarkable Washington in top form) and not a moment too soon for the audience, either, who seemed to be agitating in wonder why nearly an hour had passed without him appearing on stage. Fortunately for them, about an hour was cut from the now four hour production, most of which was from scenes preceding Hickey’s arrival. But this is not the Hickey the bar rats know and love: he’s sober! What’s worse, he tries to get them to ride the wagon with him. Nothing is worse than a righteous former (fill in the blank: drinker, smoker, addict . . . ), but the only ones who see through it all are Slade and the teenage boy Don Parritt (Broadway newcomer Austin Butler, who fares admirably), who’s come hoping to find a father figure in Slade.

David-Morse, Colm-Meanery, Danny-McCarthy, Denzel-Washington

Hickey encourages the men (and women) to give up their “pipe dreams” and the daily delusions upon which they thrive. He insists they will never accomplish anything unless they abandon the alcoholism in which they’re hopelessly mired. He believes that since he was able to give up drink that they can too, ignoring that each man has his own, complicated reason for his problem. But he’s a salesman, and he sells them all on the idea that they can recover with simple will power. And that’s just as big a pipe dream as the fantasies they’ve been harboring. When it’s revealed that Hickey hasn’t actually turned his life around, but instead has murdered his devoted wife, their brief moment of hopes is completely shattered. The next day they’re back at their tables, drunk. Same as it ever was.

The problem for Hickey—which we see etched deeply into Washington’s face, allowing us to witness his inner turmoil—is that he’s so narcissistic he doesn’t understand anyone’s pain but his own. The residents of the hotel/saloon embrace, and even need, their pipe dreams. In every community of addicts, the talk of a grandiose “tomorrow” is a mainstay. As the iconic alcoholic Barney Gumble (from TV’s “The Simpsons”) puts it, “that’s just drunk talk. Sweet, beautiful drunk talk.” And Hickey’s trying to take away the one thing they cherish, consciously or no.

This Iceman Cometh is all about Denzel. He’s the reason large swaths of the audience (many evidently unfamiliar with O’Neill) buy tickets, and the play is edited to make it his showcase (which will likely result in him landing a number of Best Actor awards). This focus appears to be frustrating for some of the other actors, as quite a number try to step up their performances to stay on par with Washington. That’s a mistake, because it takes them out of character and diminishes the play’s overall message. Nonetheless, the overall production is solid and well delivered, despite it being a must-see based solely on Washington’s performance in such an iconic, classic role.

The Iceman Cometh. Through July 1 at the Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre (242 West 45th Street, between Broadway and Eighth Avenue). Three hours, fifty minutes, with two intermissions and one pause. www.icemanonbroadway.com

Photos: Julieta Cervantes