Cast of King Lear. Mimi Ndiweni in white as Cordelia, Sir Antony Sher in throne as King Lear

by JK Clarke

While there’s nothing wrong with the trend of altering classical theater with a modern or minimalist slant, the downside is the infrequency with which newer, younger audiences get to see full-fledged, straightforward versions. Consequently, a production like the Royal Shakespeare Company’s (RSC) King Lear (at the Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Harvey Theatre through April 29) is an exciting and even revelatory breath of fresh air. What’s more, it’s a beautifully acted and staged powerhouse of a play that the legendary Sir Antony Sher has announced is his final major Shakespeare role. Sher and director Gregory Doran (the RSC’s artistic director who also happens to be Sher’s husband) combine to create a Lear for the ages.

While King Lear is ostensibly the story of a once formidable king in the throes of old age (and possibly dementia), suffering the betrayal of avaricious daughters, it is much, much more. This production makes a noble grasp at those myriad underlying themes. Shakespeare wrote the play only a few months following the uncovering of the Gunpowder Plot—which we know as Guy Fawkes Day, a conspiracy to blow up King James and all of Parliament. Amongst other motivations, the plotters wanted to prevent James’ move to unite England and Scotland into Great Britain. It is no accident that Lear chiefly concerns itself with the notion of the perils of a divided nation.

Byron Mondahl (Oswald), Nia Gwynne (Goneril), Paapa Essiedu (Edmund)

In the opening scenes, the 80-year-old king is in the process of parceling his kingdom amongst his three daughters. His favorite, Cordelia, refuses to pander to him and is summarily exiled. We are reminded at the outset that the story takes place in early, pagan Britain (approximately the eight century) as Sher’s Lear is carried onto the stage on a litter: but in this case an anachronistic pope-mobile of sorts, a large plexiglass box. The sides are dropped and he sits, overseeing the proceedings, dressed head-to-toe in grey fur, looking something like an ursine wooly man-mammoth, adorned up and down with large gold medallions. Niki Turner’s minimal set and elegant costumes are truly extraordinary. As the play progresses and Lear’s mental state and power deteriorates he is veritably deplumed, wearing fewer and fewer articles of clothing until he is nearly naked, exposing him for the man (not god) he is.

Meanwhile, a parallel storyline of sorts is taking place. The Earl of Gloucester’s bastard son Edmund (Paapa Essiedu) is nefariously plotting to take over his title, lands and money by fraudulently pitting legitimate son Edgar (Oliver Johnstone) against the Earl. Essiedu may be one of the most unique—and possibly most evil—Edmunds to ever grace a stage, with his sociopathic insouciance on pace with Othello’s nemesis Iago. A devious plotter on the page, this Edmund is almost comically nonplussed and guiltless. He responds to his interlocutors’ passions with scoffs and rolled eyes which they never catch—even shoving off Goneril and then Regan’s sexual advances as if they don’t interest him in the least. Essiedu makes the audience complicit in his misdeeds by humorously sharing his cynical disdain for whatever rube stands before him. It’s as if he has time-traveled into this land of earnestness where he doesn’t take the players seriously. Somehow, it works.

David Troughton, Earl of Gloucester

Lear, too, suffers from fits of obliviousness, as we’d expect. Taking too long to understand that he’s being betrayed by his daughters, he’s enjoying retirement through rollicking feasts with his retinue of knights and his Fool (Graham Turner). His relationship with his Fool—childishly vulgar, dressed in a dirty, white, too-revealing union suit and constantly grabbing at his nether regions—is touching and affectionate in an almost adolescent sort of way, allowing us to visit the King’s softer side, the side that adores Cordelia. When he later moans, almost as an afterthought, “and my poor Fool is hanged,” it’s far too much to digest in the midst of the chaos.

Most productions don’t, and can’t, represent the king’s 100 knights convincingly, usually using only four or five actors on stage; but Doran has brilliantly hired a local cast of 20 “Community Chorus Member” extras to fill the king’s long table. When Goneril (Nia Gwynne) complains of their carousing and excessive numbers, for once we sympathize. There are a lot of these knights and they’re always drinking, hollering and pinching backsides when in the company of Lear. Yes, he could do with a few fewer.

(Incidentally, these same “Community Chorus” members are also used to represent the downtrodden vassals of the kingdom, dressed in dirty, hooded sackcloth garments, desperate for food, and always kneeling in supplication. The added authenticity is moving.)

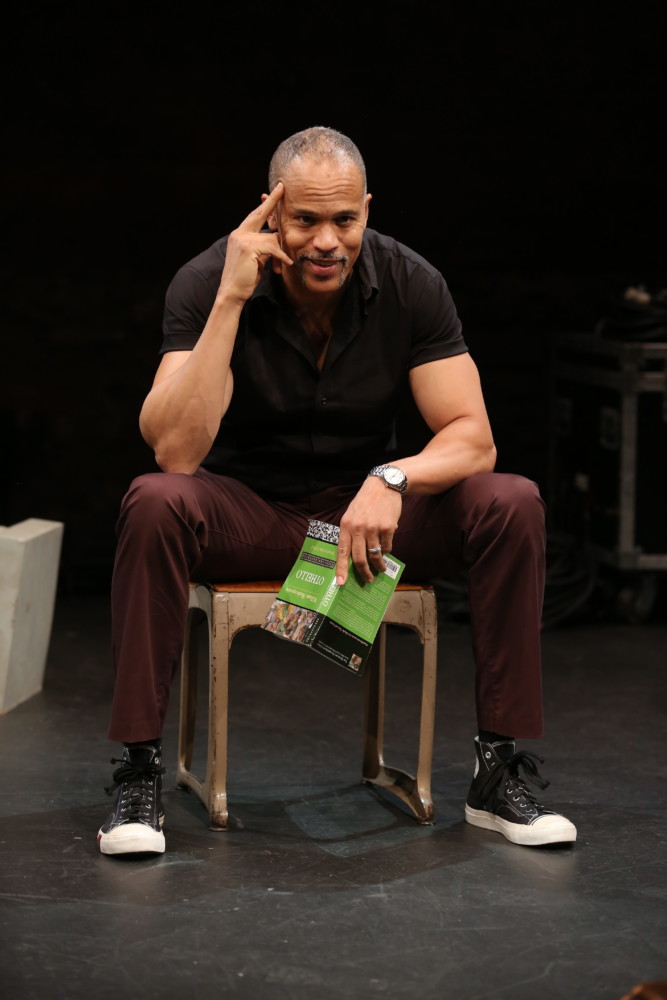

Sir Antony Sher

Gwynne’s Goneril is also rather revelatory here. As Lear bemoans Goneril’s betrayal to his middle daughter Regan (Kelly Williams), wishing suffering upon her, he turns her way suddenly and relents: “But yet thou art my flesh, my blood, my daughter.” Stunningly, we see Goneril melt into his embrace, the grimace of a daughter who has suffered her whole life from a want of fatherly love. Is she finally getting it? No. Another counterface, and now she’s a “plague sore.” The resolute fury in Gwynne’s face tells all. She’s done with him. Forever.

Other performances would stand apart were it any other production, from Antony Byrne’s earnest Earl of Kent/Caius to David Troughton’s Gloucester to Mimi Ndiweni’s touching Cordelia; even Buom Tihngang’s King of France, a small role, stood out for his obvious passion for and sense of reason toward Cordelia’s predicament. The cast, whose multi-ethnic mix is reminiscent only of The Public Theater’s company, was as immersed in the play as one can be, some disappearing so well into multiple roles that it seemed at times as if the central cast alone was well over 50 persons.

Antony Byrne as Earl of Kent, Sir Antony Sher as King Lear, Mimi Ndiweni as Cordelia

This RSC King Lear production is nearly flawless, save for some lost words from the un-mic’d actors in the cavernous but hallowed Harvey Theatre. In the pantheon of recent, notably-helmed NYC King Lear productions (Frank Langella, John Lithgow, Michael Pennington, Austin Pendleton) it undoubtedly rises above. Just for the opportunity to finally see Sher play Lear (he played Fool to Michael Gambon’s Beckettian Lear in a 1982 Adrian Noble RSC production), it’s a must-see, easily rivaling his magnificent Falstaff in the RSC’s 2016 Henry IV, Part I (part of the Great Cycle of Kings series also at BAM). If you’re a passionate about King Lear the play, or if you want to introduce someone who has never seen it to a complete and classical version of this greatest of Shakespeare’s works, this one is simply not to be missed.

King Lear. Through April 29 at BAM’s Harvey Theatre (651 Fulton Street at Ashland Place; Fort Greene, Brooklyn). Three hours, 15 minutes with one intermission. www.bam.org

Photos: Richard Termine