Corporate greed shivs Shakespeare and ignorance overshadows an otherwise powerful production of one of the all-time classics.

But here I am to speak what I do know.

You all did love him once, not without cause;

What cause withholds you then to mourn for him?

O judgment! Thou art fled to brutish beasts,

And men have lost their reason. Bear with me,

My heart is in the coffin there with [Julius] Caesar,

And I must pause till it come back to me.

— Mark Antony, Julius Caesar (III ii)

by JK Clarke

There’s no reviewing this summer’s first Shakespeare in the Park, Julius Caesar, without first addressing the unfortunate controversy that came when Bank of America and Delta Airlines backed out of their sponsorship and support of this cherished annual Public Theater event.

To paraphrase Mark Antony addressing the Plebeians, I’m not passing judgement on Bank of America and Delta, for they are honorable corporations. Yes, the honorable Delta airlines that last month kicked an entire family off a flight for refusing to give up their son’s seat. The same honorable Delta Airlines that kicked a man off a flight in April because he urgently needed to use the restroom before a flight took off. And the honorable Bank of America that last year had to pay a $430 million settlement for misusing its customers’ cash. Honorable and upright entities both.

The two corporate sponsors (not direct advertisers, mind you, and there’s a difference), seem to have taken offense at a play that was written in 1599, twenty-one years before the Mayflower set sail, and the U.S. didn’t yet exist even as a colony. A play that tells the (more or less true) story of a failed democracy on another continent more than two thousand years ago, a few hundred years before the birth of Jesus, who might have had this to say about those two enterprises: “Thou hypocrite, first cast out the beam out of thine own eye; and then shalt thou see clearly to cast out the mote out of thy brother’s eye.” Matthew 7:5

So what did The Public Theater, under its venerable artistic director (and this play’s director) Oskar Eustis do to cause such a kerfuffle? It gave the play a contemporary setting. That’s it. Choosing a Caesar who resembled Donald Trump (merely) in manner and costume was only natural for a contemporary setting (that also portrayed contemporary left wing protesters and their easily recognizable slogans). He is a sitting president who has fostered a deep concern about overreach of power and the need for the preservation of democracy, First Amendment rights and the Constitution. (I saw the play, fittingly, on the very day that former FBI director James Comey testified before Congress, strongly indicating that the President may have obstructed justice—not only is this a serious matter, but it mirrors Caesar’s own perceived overreach.) Incidentally, after Caesar is assassinated, his body and mourning family are brought out in a display more suggestive of Kennedy than Trump (widows clad in black and a 1960s era stretcher), but I guess the Delta and BofA reps didn’t stay long enough to see that part. And clearly all the whining about “assassinating the president on stage” coming from conservative talk radio and TV news pundits reveals that they didn’t pay attention during high school English either.

There is an endless supply of precedent in setting Julius Caesar in a modern era: a 1982 production at OSF in Ashland featured a Caesar who, on the heels of the murder of Anwar Sadat, strongly resembled Saddam Hussein (whom the U.S. later removed from office equally undemocratically); a Royal Shakespeare Company production in 1968 drew comparisons to Charles de Gaulle (while he was in power); and Orson Welles staged the an anti-fascist version of the play in 1937 in New York at a time when the US Government hadn’t quite decided what it felt about fascists or even Hitler for that matter, and was loathe to offend German-Americans. (Shakespeare Around the Globe, Leiter). Florida’s Governor Fuller Warren even referred, in 1950, to Senator Estes Kefauver as “an ambition-crazed Caesar” for his commision investigating organized crime. Linking controversial politicians to Caesar is simply nothing new. When I re-read the play recently I was struck by how many of the lines could be easily applied to today’s political climate, plucked from political roundtables. If anything, Eustis’s shortcoming may have been that the comparison was too easy, too on-the-nose.

But here’s the silliest part (that the ill-informed critics didn’t bother to research): Julius Caesar isn’t about assassination. No, not really. It’s a small part of the play, a lead-in catalyst. As Eustis pointed out in a post-controversy statement, it’s a tragedy about the mistake of taking a political moment into one’s own hands and destroying “the very thing they are fighting to save.” Noble Brutus is one of the most tragic figures of all Shakespeare (resembling the French Revolution’s Robespierre) who believed so fervently in the cause but smashed it to pieces by taking selfish (in the guise of heroic), drastic action. The play is really about the ensuing, unnecessary war precipitated by the assassination.

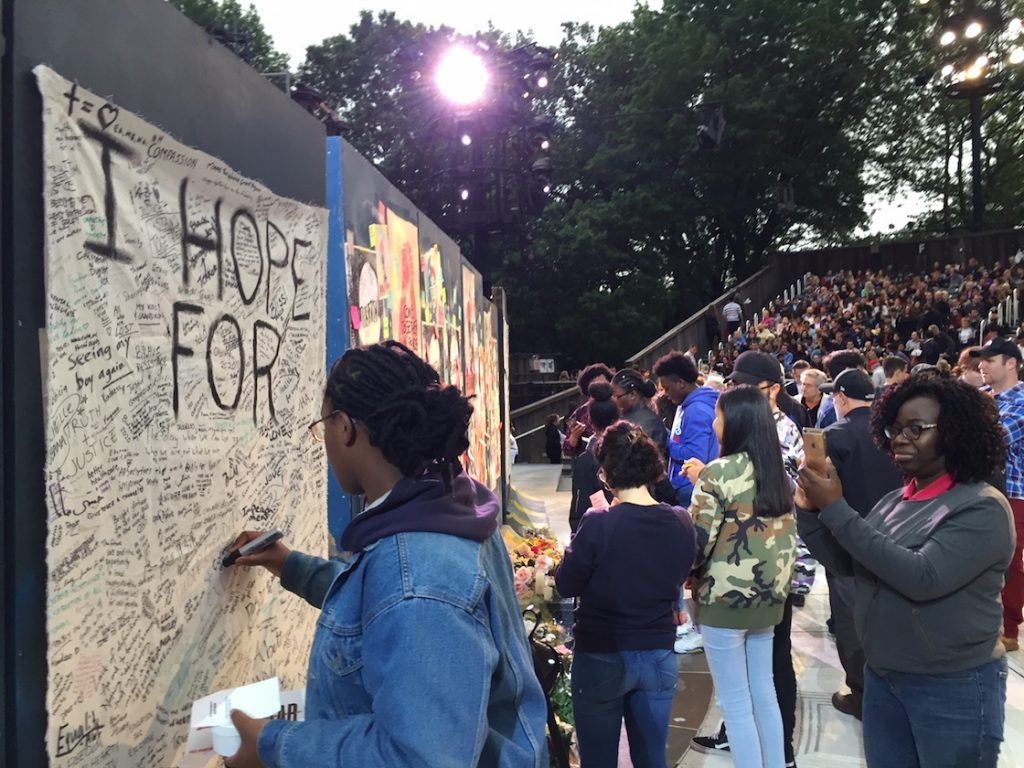

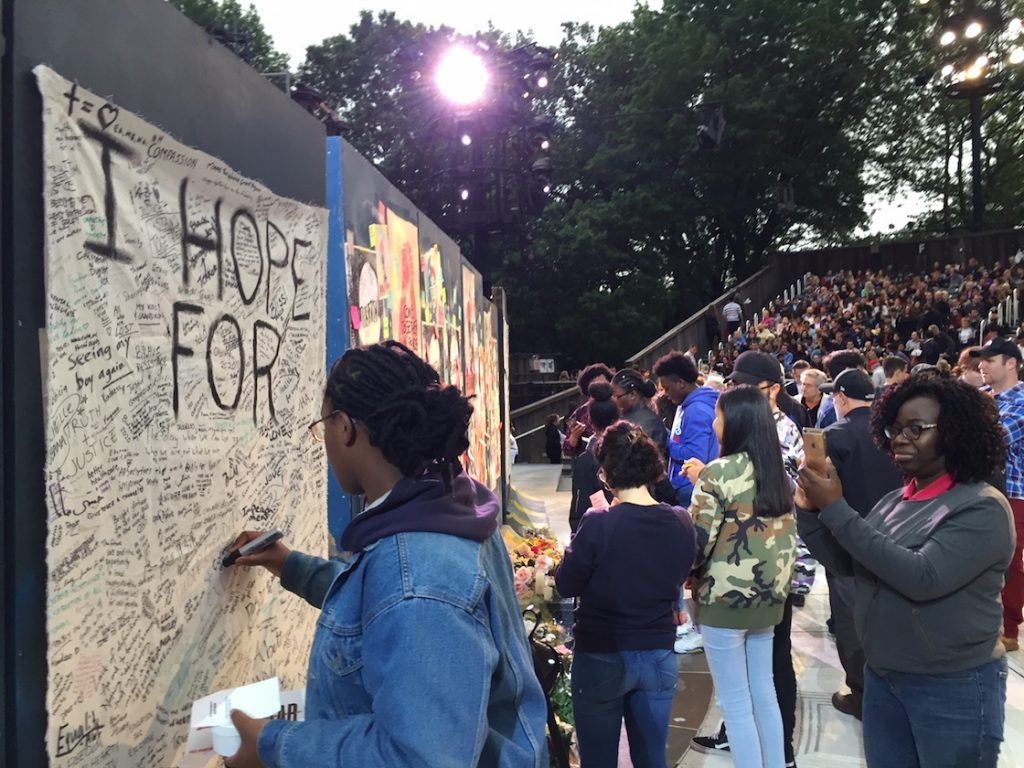

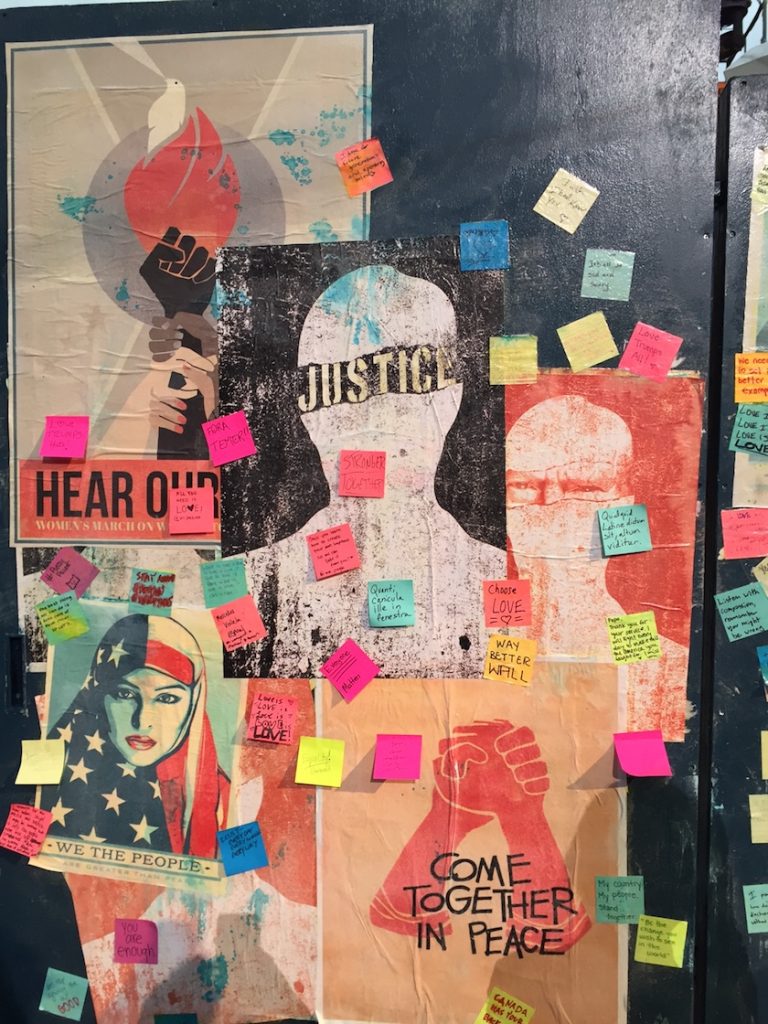

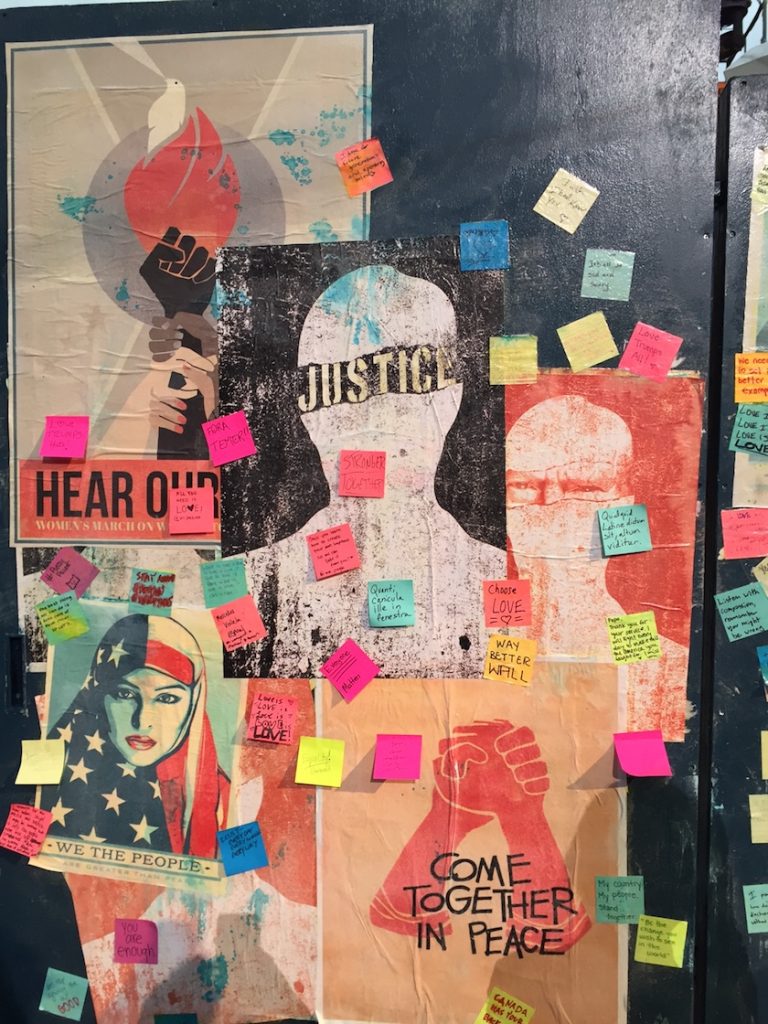

Here’s what we’re missing in all the patently unnecessary hubbub, which only serves to create additional advertising for the companies in question: a discussion of an intense, thought-provoking production. In an unusual move for Shakespeare in the Park, prior to the performance audience members are compelled to come up on stage to write on a wall reminiscent of the Union Square post-election Post-It Mourning Wall and mingle with others people who turn out to be characters: the rabble, the Roman public, who have interspersed themselves with the audience, and later shout out and eventually storm the stage; the move makes us complicit in the mob madness and violence. David Rockwell’s Brutalist set, with two giant, modular Soviet-esque concrete gears protruding out of the ground creates, along with barbed-wire ramparts, a grim, post-industrial setting perfect for carrying out countless political murders and street warfare.

Lost, too, in all the noise, are a number of terrific performances. Most notably John Douglas Thompson as a passionate, multi-layered Cassius, continuing his reign as one of the best classic theater thespians working today. Corey Stoll (whom many will recognize, ironically enough, from the first season of Netflix’s House of Cards) is a solid Brutus, determined and caring in his quest to save the democracy. And in keeping with a theme, Caesar’s sycophantic side-kick Mark Antony is played as a woman (Elizabeth Marvel, who transforms deliciously from tracksuit-wearing toadie to fierce general in what seems like mere moments) with echos, linguistic and otherwise, though far more sophisticated, of Trump mouthpiece Kellyanne Conway.

Productions of Julius Caesar can be difficult to sit through. Though laden with memorable, oft-quoted lines (“cry havoc and let slip the dogs of war!”), it lacks the moments of levity so prominent in Shakespeare’s other tragedies, and the heaviness of the political message can drag. It can’t be easy to produce. But this version, at two hours with no intermission, moves quickly enough and feels very thorough, making it a solid, well produced show that should please first-timers.

Yes, this was certainly a production designed to raise temperatures. And it did. Sitting next to us, a tourist couple who’d apparently heard about the wonders of this iconic New York summer event and stood in line all day for free tickets, glowered. And another man, about an hour in, walked down from his seat toward the exit, flinged his program toward the stage and left. I can only think these folks had never seen or read the play before, which, quite frankly, is probably a good thing to do (at least a synopsis) before investing any time or energy into a play as complex as Julius Caesar. In any case, the show was free! I can understand the anger if they’d paid Broadway ticket prices, but these folks paid nothing for a first rate production.

But, to borrow again from Mark Antony, “the most unkindest cut of all” came from the corporate backers (Delta and BofA and even American Express, but to a lesser degree) who adore engaging in the clever sort of aren’t-we-cool advertising that theater sponsorships provide. The conceit is that they “support the arts” and are one with the enlightened, moneyed, theater-going public. However, the very idea, the very horrifying idea, that they have decided the pull their sponsorship based on what they’ve deemed “objectionable content” is nothing more than the basest form of censorship and is the very reason why federally subsidized, national endowments for the arts (by the People) are an absolute necessity. It is not up to private businesses like Bank of America and Delta Airlines to determine what constitutes “art,” good or bad. Either they support the arts or they don’t.

Everyone is free to disagree with the director’s artistic choices. That’s the case in every production. But it is up the critics and the people who see the play to make that determination for themselves, not for the sponsors to use financial leverage as a truncheon to enforce their political will. In any case, to object to content that has existed for 400 plus years is the height of lunacy. This is Shakespeare, for god’s sake! Just go see it. Decide what you think for yourself. Don’t let a self-serving company decide for you. And as for The Public and any other artistic organizations: it might be time to sever ties with these particular corporations and lay some ground rules about future productions with your other affiliates. They don’t deserve you if they can’t abide you.

Julius Caesar. Shakespeare in the Park presented by The Public Theater. Through June 18 at The Delacorte Theater (81, Central Park West). Two hours, no intermission. Free. www.publictheater.org

Photos: Joan Marcus

Additional Photos of Pre-Show Theater and stage by Craig Hymson