Book review by Samuel L. Leiter…

Casual notes on show-biz books, memoirs and studies, dust gatherers, and hot off the presses.

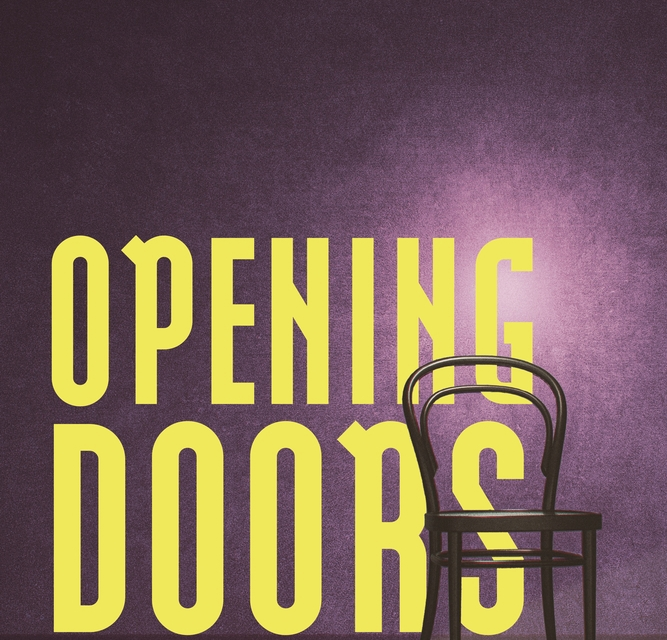

John Doyle, Opening Doors: Reimagining the American Musical (London, New York: Methuen/Drama, 2025). 235pp.

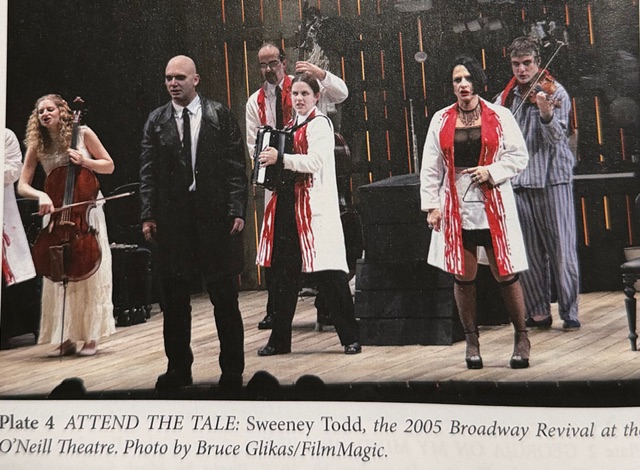

Anyone fortunate enough to have seen the 2005 Broadway revival of Stephen Sondheim’s groundbreaking 1979 musical Sweeney Todd will recall how brilliantly it scaled the show down for a cast of 12 that not only acted and sang their roles but served as the orchestra, each playing one or more instruments. Patti LuPone’s Mrs. Lovett, for example, performed on the tuba, not to mention chiming on the bells and percussion,

This signature production was the brainchild of Scottish-born director John Doyle, born in Inverness in 1953, who quickly made a glowing name for himself as the inventive genius behind a series of musical revivals expressing his “essentialist” approach. In these, an otherwise complex show was stripped down to its essentials, including not only its musical accompaniment—in which a conventional orchestra was replaced by actor-musicians—but visually, with creatively simplified sets, costumes, and lighting.

Now 72, Doyle, who famously exploited his unique vision during his six-years tenure (2016-2022) as artistic director of Off Broadway’s Classic Stage Company, has just published a valuable, highly accessible memoir in which he outlines both his prolific career and his practical and theoretical views. Titled Opening Doors: Reimagining the American Musical, it is much more than the subtitle suggests.

Born into lower-middle class circumstances in the Scottish highlands, Doyle recounts his hardscrabble youth, his youthful theatrical experiences as an actor-singer (beginning at the Inverness Opera Company with Og the Leprechaun in Finian’s Rainbow!), his university years (Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama and the University of Georgia), the influences on him of his professors, and his slow but steady ascent into professional recognition as he gained facility directing plays in UK regional theatres.

Eventually, he enjoyed success as artistic director—a position he held six times and whose varying responsibilities he explores—at a series of important institutions, before plunging into fulltime freelance work. His resume includes not only a full panoply of musicals but traditional plays, both classic (lots of Shakespeare) and modern (Brecht is a favorite), and lots of opera, often at the most prestigious venues, like the Sydney Opera House. Those who know him only from his New York work will find the appendix listing of his numerous productions seriously eye-popping.

Doyle, proudly Scottish, keeps his private life to a minimum, but does allude to such things as his musically talented mother’s influence and to his marriage to Jacqui Doyle, which produced his beloved daughter, “Beccy.” The marriage dissolved (amicably) when he—like so many others these days—reaching middle age, accepted the fact he was gay, eventually marrying a man he’s been with for over two dozen years.

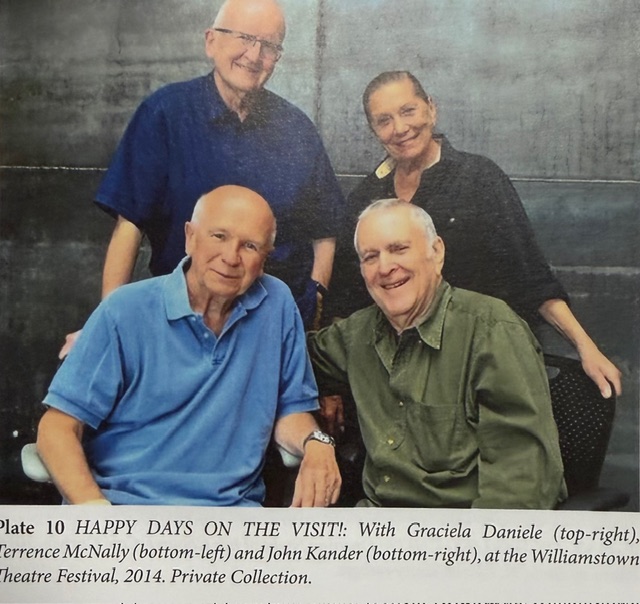

Doyle offers numerous amusing and instructional anecdotes, like a fascinating research trip to the USSR in the 1980s, as well as a decent stock of Sondheim stories. He discusses what he means by “classic” theatre, discourses on the power of music (and orchestration) in theater, and describes both his (selected) hits and flops. Many familiar names with whom Doyle worked, from Bernadette Peters to Chita Rivera, pop up, with tales to match. Many shows are recalled, with particularly detailed accounts of his five Broadway outings, Sweeney Todd (2005), Company (2006), A Catered Affair (2008), The Visit (2015), and The Color Purple (2015).

Through it all, Doyle maintains an even-handed, self-deprecating tone (even when delighting in his greatest successes), rarely talks about anyone disrespectfully, expresses astonishment to find himself working with household names, and, in general, seems a chap with whom one would enjoy having a brew.

Although anyone with a love of theater will find much to appreciate, Opening Doors will be of special interest to fans of modern musical theatre, and, especially, to practitioners, be they actors, singers, directors, dancers, designers, producers, or musicians. Doyle tells the story of his professional life, how he created many of his shows (experimental and traditional), the conditions under which he often worked, his rehearsal methods, and how he and his colleagues overcame the typical problems that arise in production. His explanation of the conditions required to direct opera for a major institution are priceless. He often comments wisely on the financial and other issues of the contemporary theater, both profit and non-profit. Doyle’s attitudes toward nontraditional casting and directorial ethnicity and sexuality also get your attention. His love for teaching—of which he’s done his share—gets space as well. In his final chapter, “Opening Doors,” Doyle considers opening doors to subjects such as “politics in the theatre,” “‘essentialism’ in theatre-making,” “those who have not been given a fair opportunity,” and seven similarly thoughtful topics, including, as he calls it, “me.”

Given his limited number of Broadway shows, and his substantial output in regional institutions or the small confines of the CSC, it’s doubtful if his name has the clang of someone like Hal Prince or Jack O’Brien, but that doesn’t mean it’s any the less important than the books those Broadway directorial giants wrote.

Doyle himself accepts the fact that his signature style, the actor-musician musical, which has apparently influenced many others seeking new and less expensive ways to do such shows, may brand him as a one-trick pony. And, to be honest, some critics and theatergoers are not fervid fans of his style, or of having an advance idea when going to one of Doyle’s musicals of what they’re likely to be in for. But, even if only in a small way, his influence has been unmistakable. And his book is only partly about his essentialist innovations, a great deal more of it being about the imaginative ways in which he and his talented co-artists resolved multiple problems in conventional opera and dramatic productions.

Simply stated, Opening Doors, which includes an index and 16 photos, is a worthy book tnat will surely open many doors.