By Samuel L. Leiter…

Casual notes on show biz books, memoirs, and studies, dust gatherers and hot-off-the presses.

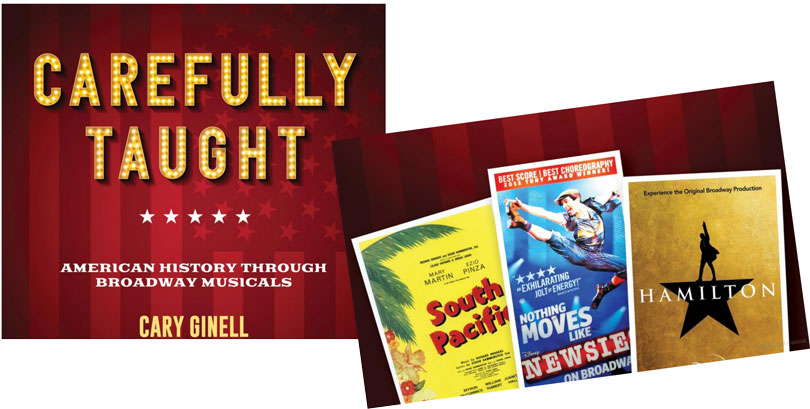

Cary Ginell, Carefully Taught: American History Through Broadway Musicals (Essex, CT: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2022). 274pp.

Cary Ginell, editor of the Broadway Musicals: Show by Show for Applause, has found a useful way to slice the Broadway musical pie. His interesting but flawed 2022 book, Carefully Taught, whose title comes from a song in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, describes, one by one, 39 shows, many of them hits, or, at least, well known; on the other hand, some are not only obscure but were never seen on a Broadway stage, despite the book’s title. This is the kind of book that, for all its usefulness as a way not only to appreciate but learn from musical theater, is bound to bump into obstacles when it comes to opinions on the examples chosen.

Many shows serve the author’s purpose well, being based on important historical situations or the lives of significant Americans, even if the facts are fiddled with for dramatic effect. Others skirt the “historical” framework by their preoccupation with social issues that once roiled the nation. Thus, we have shows based on actual history, featuring familiar names and happenings, and shows that are purely or partly fictional, although reflective of historical circumstances, offering Ginell an opportunity to expand on the political or social backgrounds depicted. Ultimately, one begins to wonder why some shows made the cut, while others, with what might be considered stronger reasons for inclusion, are overlooked.

The first item we get in each chapter is a basic primer on the show’s provenance, informing us of its who, what, when, and wheres. A succinct “Historical Background” follows, where the show’s context and meaning are clarified, after which comes a section titled “Production Notes,” providing background on the show’s history, anecdotes included. Finally, there’s a section called “Score,” in which Ginell briefly highlights the musical contributions. Most of these shows have been written about extensively, so much of the content is familiar, and sometimes disappointingly so. Hair, for example, is so superficially covered as a plotless show that there’s no mention of it leading characters and their dilemma.

Of course, part of Ginell’s project is to reveal the distinction in many shows between what is “real” and what is “fictional,” but space limitations keep such discussions minimal. The book is organized in crudely chronological fashion according to when the events depicted occurred, beginning with 1776 and Hamilton, and ending with Hair and Assassins. This suggests that nothing pertinent to American history after the Vietnam war and the flower children and the attempted assassination of Ronald Reagan was worthy of musical theatre treatment.

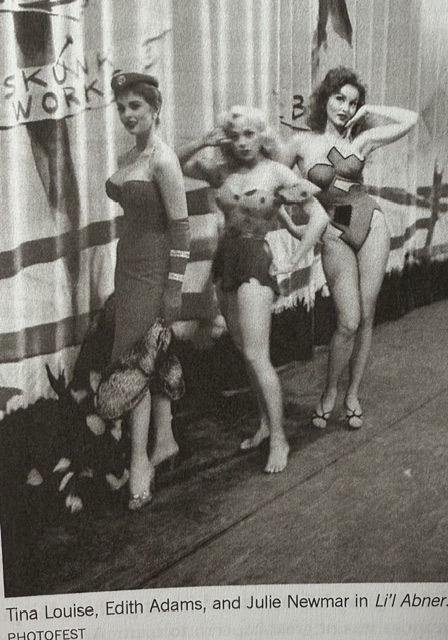

To a degree that’s true, as few musicals of the past forty years, say, deal directly with contemporary issues, other than, say, LGBTQ+ topics, as in Rent or The Prom. If shows like The Music Man and L’il Abner deserve inclusion, surely something of more contemporary pertinence might have been included. There certainly were such shows Off Broadway, like the satirical Clinton: the Musical, seen in 2015 or First Lady Suite (1993). Instead we get Freedom Riders: The Civil Rights Musical, which received five performances at Theatre Row in 2017, or Baby Case (about the Lindbergh kidnapping), in 2012. Both were Off-off Broadway festival offerings, not given regular runs, and neither has even a cast album to mark its existence.

The same questions about their inclusion arise about several other shows, while one might argue that shows Ginell ignores—like Mr. President, Call Me Madame, or, even earlier, George Washington, Jr., and others—deserve a look. In some cases, the history evoked is that of show business, which allows Annie Gets Your Gun, Gypsy, The Will Rogers’ Follies, and Million Dollar Quartet to get chapters, but Ginell has to wiggle around definitions about why some show business icons—so many during our juke box craze—are not. Even George M., about a true American icon, is ignored.

Then there are the occasional eyebrow-raising comments, such as that Fiorello! (1959) was “the first time a major Broadway musical was devoted to a famous American subject personally familiar to members of the audience” (p. 138). So where does that leave George M. Cohan’s I’d Rather Be Right (1937), about FDR? Or the statement that L’il Abner (1956) was “a Broadway first” (p. 219) when it came to putting a popular comic strip on stage. What about Little Nemo (1908) or Blondie (1950)?

The idea behind Carefully Taught is sound, and some of it does a satisfactory job of making clear how historical subjects of a political and/or social nature have been handled on the (mainly) Broadway stage. But too often anyone with a modicum of knowledge regarding modern musical theater will question many of the selections, and take issue with a few remarks that push credibility. The book is easy to read and can be recommended for readers relatively unfamiliar with musical theater but serious fans are likely to be disappointed, given how much outstanding criticism and history has been previously published about so many of these shows.