Book review by Samuel L. Leiter

Casual notes on show-biz books, memoirs and studies, dust gatherers, and hot off the presses.

Barbara Wallace Grossman, A Spectacle of Suffering: Clara Morris on the American Stage (Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009). 321pp.

She was considered the greatest “emotional” actress of the late 19th century, an era when such designations were widely used to characterize female stage artists. She was also called “queen of spasms,” not only because of her emotional eruptions but because she suffered constantly from back pain, among other causes, which affected her onstage behavior. Her name was Clara Morris and, during her fascinating career, this proto-feminist star not only achieved great artistic highs, but suffered painful lows, both artistic and personal.

Once a household name, especially in the 1870s and 1880s, but now largely forgotten except among theatre historians, she’s the subject of a thoroughly well-researched, expertly written biography of Morris (1848-1925), published 16 years ago by Barbara Wallace Grossman, Professor of Theatre at Tufts University. Morris, whose later years saw her turn from acting to writing, published three memoirs, but none tell her story with the kind of comprehensive detail and analytical insight brought to the task by Grossman. Morris also kept a 54-volume diary covering 1868-1924. Despite significant lacunae it forms an extremely valuable resource in Grossman’s reporting, as does the unpublished research of an earlier researcher, George T. MacAdams, who left it behind on his death in 1929.

Grossman’s study begins with Morris’s difficult childhood in Toronto, Canada, where she was born into a bigamous marriage. She was raised with little schooling in Cleveland, OH, by a mother to whom she remained devoted all her life. She made a youthful entry into the world of theatre as a ballet girl and stock company player where her talents were eventually noticed and given greater opportunities.

She debuted in New York in 1870 under the management of Augustin Daly, who was then emerging as one of the period’s most successful producers, directors, and playwrights. In his stock company she became—not without conflict over roles—a leading lady in melodramatic vehicles that exploited her capacity for playing emotionally volatile women, bathing the stage in tears and wringing them by the handkerchief-full from audiences as well. Grossman describes Morris’s various professional conflicts with Daly, and her professional relationship with another leading producer, Albert M. Palmer. She performed her hit roles both in New York and, as a necessary part of the business, on the road, gaining fame in countless cities, big and small.

However, as tastes changed, she could not sustain the pace. Her repertory remained rather static and small as the years passed, with such plays as Camille, Alixe, Miss Multon, Odette, and Renée de Moray, often from French originals, being done repeatedly, while new plays were ignored. Inheriting the position of America’s greatest Camille from Matilda Heron, she was closely associated with it despite her own recognition of its flaws. Grossman provides an extensive account of Morris’s Camille, one of the book’s most significant contributions, just as is her discussion of Morris’s unsuccessful Lady Macbeth.

Although she often had to defend herself from attacks on the “fallen women” she frequently played, her own life was relatively free of scandal; she remained unhappily married to a difficult husband, Frederick C. Harriott, who managed her career and with whom she often quarreled, as reported in her diaries, where she used words like “cruel” to describe him.

Most debilitating of all were her many bouts of illness, often causing audiences to wait for her during long intermissions as she recovered from pain—usually from spinal problems—when not canceling shows outright. Her diaries show a decades-long dependence on morphine (legal at the time), which became difficult to obtain once laws were passed restricting its use.

When regular theatrical engagements became difficult to obtain in the 1890s, she turned to vaudeville, where she could earn even more money than in the legitimate theatre doing less demanding one-acts, beginning with a piece called “Blind Justice.” She was one of the earliest major legit stars to take advantage of this new source of income, which others disdained for a while (like commercials in later years) as below their dignity.

When even vaudeville engagements became too difficult or unavailable, she took up writing, publishing not only novels and short stories, but newspaper columns and hundreds of articles on topics of the day; many, of course, were about the theatre and acting. Despite her ailments, including loss of her sight, and both marital and financial problems, she maintained a positive spirit and was able to repurpose herself and survive with dignity.

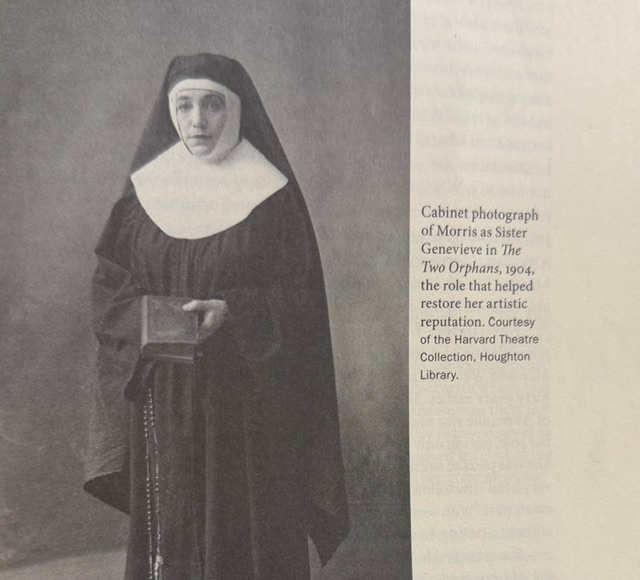

Grossman depicts a woman of talent who had obvious drawbacks (she failed at Shakespearean roles, most seriously Lady Macbeth), and, while pretty, was not a great beauty. She was, though, a model for other women of the Gilded Age, one whose acting style shifted from advanced to outmoded and overwrought, but who, while it lasted, was the sine qua non of the school of emotional realism. However, she made something of a brief comeback playing, to high praise, the minor role of Sister Genevieve in a 1904 all-star revival of The Two Orphans, where her dialogue was limited and her acting restrained.

We see from Grossman’s book how precarious was life upon the wicked stage in the 19th century, when theatres and lodgings on the road were often filthy and cold, food limited and barely edible, and one-night stands meant perpetual traveling from nondescript town to nondescript town on uncomfortable trains.

Grossman has done theatre history a significant service in preserving Morris’s legacy in this exhaustive recounting of her invaluable contributions. More than as a “melodrama queen,” Clara Morris was American theatre royalty whose life deserves to be remembered. Thanks to Grossman’s A Spectacle of Suffering, that is guaranteed.