By Samuel L. Leiter

Casual notes on show biz books, memoirs, and studies, dust gatherers and hot off the presses.

Christopher Byrne, A Man of Much Importance: The Art and Life of Terrence McNally (New York: Applause Theatre and Cinema Books, 2023). 378 pp.

Review #53

Nowadays, the sexuality of public figures—regardless of their accomplishments—is often among the first things we know about them, especially if they don’t conform to heteronormative expectations. Thus, in Christopher Byrne’s imperfect but informative and entertaining biography of Terrence McNally, A Man of Much Importance, the late playwright’s homosexuality courses through the text like a river. This is only natural, considering its significant, though not exclusive, presence in his prolific body of work.

McNally was born in St. Petersburg, FL, in 1938, but raised mostly in Corpus Christi, TX, a cultural backwater from which he couldn’t leave fast enough when he was accepted into Columbia University. He died of COVID-19 related illness in 2020, although he had long suffered the effects of lung cancer. He was around so long and his plays, ranging from avant-garde exercises to full-blown commercial hits, arrived so regularly it was almost possible to take his presence for granted. But as revealed in Byrne’s substantial, yet necessarily, selective, tome, his career was remarkable, not only for its prolificity, but—regardless of its flops (And Things That Go Bump in the Night, for one)—for its sustained level of excellence.

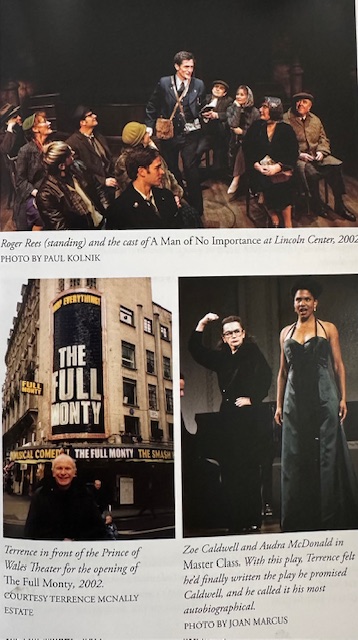

As the book’s title, inspired by McNally’s musical, A Man of No Importance, suggests, he was indeed of much, even vast, importance to the American theatre, writing plays not only depicting life in the gay male community, but of the worlds of theatre and opera, and, more broadly, in terms of human connection, as one of his titles puts it, about Love! Valour! Compassion! Winner of five Tony Awards, he wrote not only conventional plays but the books of major musicals, like Kiss of the Spider Woman and Ragtime. He scored on and off Broadway with works such as The Ritz, It’s Only a Play, Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, Lips Together, Teeth Apart, The Lisbon Traviata, A Perfect Ganesh, The Full Monty, Master Class, and too many others to mention. An opera obsessive since boyhood, he even wrote libretti, like the successful Dead Man Walking, adapted from Sister Helen Prejean’s book about a Death Row convict.

His remarkable career was for many years tied closely to the Manhattan Theatre Club and its artistic director, Lynne Meadow, although the relationship was at one point disrupted when Meadow found herself unwilling to produce one of McNally’s plays. Byrne tells the story with grace, just as he does all the many other fascinating events that filled the fecund playwright’s days. Among these are those related to McNally’s activism on behalf of the gay movement, particularly following the AIDS crisis.

Byrne, contributing theatre editor for Gay City News, writes sensitively about McNally’s private life, referring to him throughout, with one exception, I believe, as “Terrence.” There is substantive treatment of McNally’s romantic relationships, including playwright Edward Albee. Although he eventually married the love of his life, Tom Kirdahy, a lawyer who transitioned to successful producer, McNally also had an intimate affair with female playwright Wendy Wasserstein, which may come as a surprise to some readers; it did to me, I admit.

Abundant examples are given of McNally’s working methods, particularly his passion for collaboration during rehearsals, although this sometimes led to problems. He was compulsive about rewriting, and preferred to do so on the spot, even typing away at rehearsals. His preoccupation with making alterations, even in the latest stages of rehearsal, could drive some actors crazy, but most appear to have welcomed his devotion to perfecting his words. Byrne offers numerous anecdotes about working with him, pulled from interviews and feedback with luminaries in the playwright’s circle, including Nathan Lane, Patti LuPone, Jason Alexander, Chita Rivera, Jack O’Brien, Lynne Meadow, and Audra McDonald. He also was no stranger to controversy, as witness the ruckus kicked up by his Corpus Christi in which Jesus and his disciples are gay

Byrne’s approach is more journalistic than academic, and, while there’s an index, there’s no documentation of his sources. In fact, other than mentioning McNally’s own semi-memoir, Selected Plays: A Memoir in Plays (2003)—an unconventional memoir framed around selections from his writings—he never cites the existence of two academic studies of his subject: Peter Wolfe’s The Theater of Terrence McNally: A Critical Study (2013) or Raymond-Jean Frontain’s The Theater of Terrence McNally: Something About Grace (2019). The size of McNally’s oeuvre is so large, it’s understandable that Byrne is unable to cover, much less mention, everything, so it’s disappointing not to see even a brief bibliography for those seeking further background. Fortunately, though, he provides a chronology of McNally’s plays, musicals, operas, television scripts, screenplays, etc.

There’s much to be learned from Christopher Byrne’s friendly survey of this dramaturgic titan’s life and career; based on what I know of the other books I mentioned, I’d put my money on it being much more widely accessible to the general reader. I’m compelled, however, to note that whoever proofread A Man of Much Importance overlooked too many slipups, many of the tiny sort the eye can easily miss but a few that pop off the page, like Ballets Rousse for Ballets Russe (p. ix), or Willy for Winnie Holzman (p. 225). I can’t imagine what Terrence McNally, the verbal perfectionist, would have done if he’d seen these!