Review by Carol Rocamora…

A riveting revival of this devastating melodrama shakes the rafters of TFANA

“You want the truth? You can’t handle the truth!”

It’s not often that a review of a play by Norwegian dramatist Henrik Ibsen begins with a famous quote by film star Jack Nicholson, is it?!

But Nicholson’s cry (in a 1992 film called A Few Good Men) succinctly summarizes the theme of The Wild Duck, Ibsen’s riveting melodrama wherein “a few good Norwegian men” confront the same question more than one hundred years earlier, in 1884. What is the value of truth – most importantly in the family, as well as in friendship? Does the truth make for a happier life? Is it better to live a lie than to live a truth?

Written while living in Europe, Ibsen’s exile from his homeland intensified his perspective on the narrowmindedness, hypocrisy, and rigidity of the Norwegian middle class. That became his theme for A Doll’s House, Ghosts, and An Enemy of the People, plays he wrote in the early years of his exile. When it came to The Wild Duck, however, his vision became more existential.

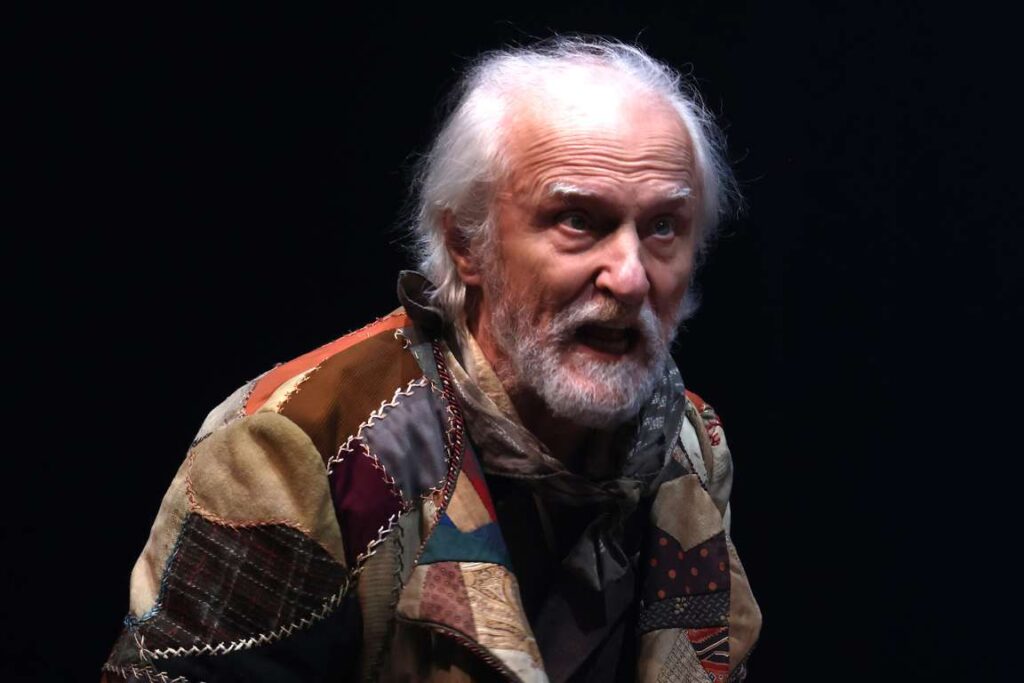

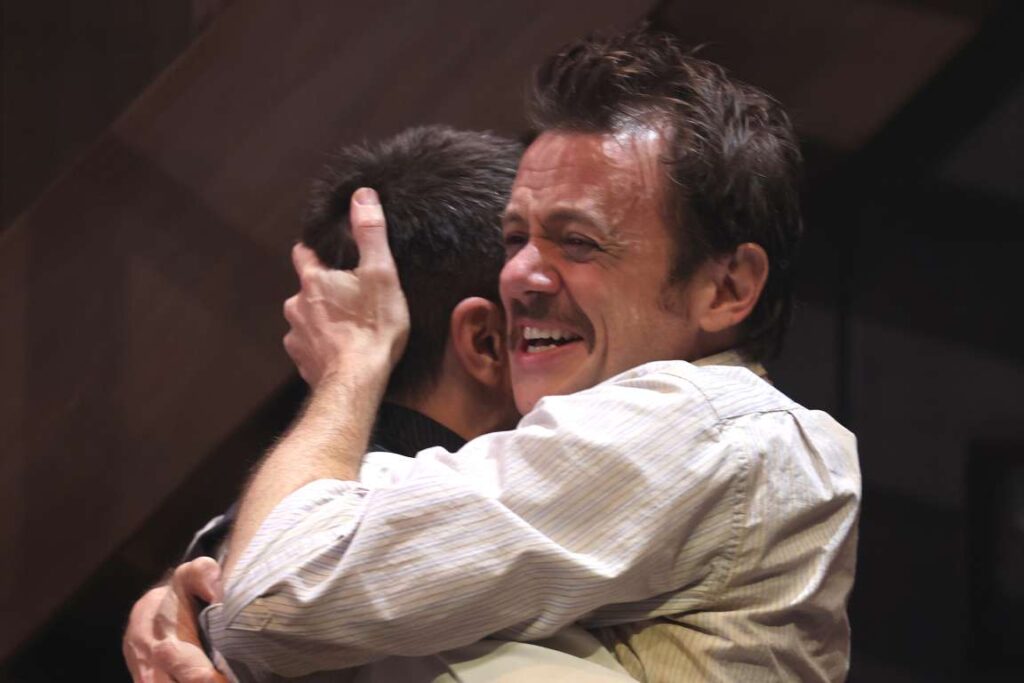

The Wild Duck tells a split-screen story of two families – the Werles and the Ekdals – whose secrets and lies in their past and present interconnect, with violent and tragic results. In the first of five gripping acts, powerful industrialist Hakon Werle (Robert Stanton) is throwing a grand party, at which his son Gregers (Alexander Hurt) appears after a fifteen-year self-imposed exile. There, Gregers encounters his former classmate and friend Hjalmar Ekdal (Nick Westrate), and learns that Hjalmar is happily married to Gina (Melanie Field), a former servant in his father’s household. Obsessed with suspicion that his father once had an affair with Gina, Gregers decides to “save” his friend from living a lie, and moves in with Hjalmar, Gina, and their fourteen-year-old daughter Hedvig (Maaike Laanstra-Corn), who is going blind. Also living with them is old Lieutentant Ekdal, Hjalmar’s father (David Patrick Kelly) who spends his time in the loft hunting animals he keeps there – including rabbits, birds, and (yes) a wild duck, Hedvig’s beloved pet.

Ultimately, Gregers reveals the truth to Hjalmar– that his father Hakon Werle did have an affair with Gina (now Hjalmar’s wife) and that Hedvig may indeed be Werle’s daughter. Traumatized, Hjalmar cruelly rejects Hedvig’s desperate pleas for love. Still intent on his crusade to have all the members of this traumatized family embrace the truth, Gregers tells Hedvig to take her grandfather’s gun, climb up to the loft, and shoot the wild duck. By destroying the thing that is dearest to her, she will prove to her father how much she loves him. (You can guess the rest – no spoiler alert.)

Don’t be surprised if I tell you that the above plot synopsis is the “short version.” (Remember, this is Ibsen). There’s a whole backstory about a variety of other issues: Greger’s fifteen-year absence, Old Ekdal’s complicated past (including a prison sentence), Greger’s mother’s tragic death, Hakon Werle’s encroaching blindness, and so on on – too long to recount here.

The characters are just as complex as the plot. Gregers preaches “living in truth” as the path to integrity and freedom, but he doesn’t seem to see – or care about – the devastation he causes. Ultimately, as we discover, his motivation is not just to reveal the truth, but rather to get even with his father for the pain he caused his mother, who died knowing of her husband’s infidelity. So despite his relentless rhetoric about serving the truth, it turns out that the self-righteous Gregers is lying about his own intentions.

Nor can we find pity for Hjalmar. Self-centered, histrionic, moody, he dreams of becoming an inventor – but that’s also a kind of “life-lie,” since his amorphous plans have little chance for fruition. Moreover, his cruel rejection of Hedvig’s desperate need for his love make him an equally unsympathetic character.

The female characters in The Wild Duck fare far better in Ibsen’s hands. Gina, a young, helpless servant, was taken advantage of by Hakon Werle, her employer. She ultimately marries Hjalmar, and has selflessly devoted her life caring for him. As played by Melanie Field, she displays the same warm, sensible qualities she brought to the character of Sonya in Uncle Vanya last season, and elicits our profound sympathy. So does Maaike Laanstra-Corn, who gives a deeply moving performance as the loving, childlike Hedvig, who meets a cruel fate because of her father (and the author.)

As this all weren’t complicated enough, we come to the play’s title: The Wild Duck. Why is it called thus? Ibsen tantalizes us with this question. The backstory is that the wild duck was shot and fell to the bottom of the sea, but was rescued by Old Ekdal’s dog and placed in the loft along with the other animals. Is Hedvig the wild duck? Or is it the family? Or truth itself?

Expertly directed by Simon Godwin, the play flashes by like “the speed of life,” as he calls the exciting pace he sets to drive this melodrama to its devastating conclusion. His company is uniformly excellent; among other characters there is also Dr. Relling (Matthew Saldivar), who coined the phrase “life-lie” that sits at the heart of the play’s theme. Andrew Boyce’s set features the interior of Ekdal’s home with a soaring ceiling and stairs leading to the loft that holds the mystery of the play. There is beautiful Norwegian music during scene changes played by a live musician (on violin and Norwegian-type dulcimer), adding a rich dimension to the atmosphere.

Ultimately, for me, the truth about this play is that – though Ibsen himself condemns moral hypocrisy – he himself is a stern, judgmental moralist, showing little compassion for the complexities of human behavior. As such, Ibsen is as unforgiving and harsh to his characters as Gregers.

Still, Ibsen addresses an existential threat that is universal. As director Simon Godwin asks: “How much truth can we take? How much truth do we want? How much truth can we bear? These are the fundamental questions that this riveting, “take-no-prisoners” play poses to us all.

Playwright Edward Albee also addresses these questions in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf, his 1962 masterpiece, in which a couple (George and Martha) create an imaginary child in order to survive in their marriage. At one point, they have the following exchange:

Martha: Truth or illusion, George; you don’t know the difference.”

George: “No, but we must carry on as though we did.”

Ultimately, George announces that the child is dead, so that they can face the truth, save their marriage, and carry on with their lives.

If only Ibsen had shown his characters as much compassion…

The Wild Duck, by Henrik Ibsen, directed by Simon Godwin, at Theatre for a New Audience, now through September 28.

Photos: Hollis King / Gerry Goodstein