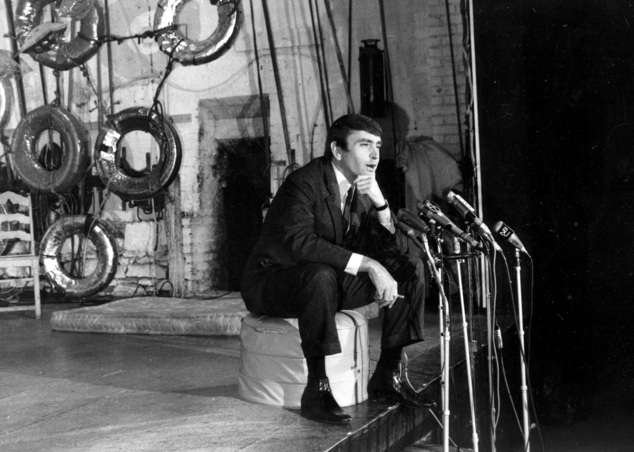

In this May 2, 1967, file photo, playwright Edward Albee, winner of the 1967 Pulitzer Prize for drama, for his play “A Delicate Balance,” talks to reporters during a news conference at the Cherry Lane Theater in the Greenwich Village section of New York.

by Beatrice Williams-Rude

As the world mourns Edward Albee I’m reminded of a reading of Everything in the Garden, which I saw at St. Clement’s in Manhattan, June 21, 2010, the first in what was to be a series of “Plays You Should Know but Probably Don’t.”

In the middle of the last row were four people sitting beside one another. Liz McCann, Albee’s longtime backer; Albee; playwright Joe Westerfield and I. There were empty seats on both sides of us.

I’d helped Liz up the outside stone steps (not recognizing her), Joe had half carried her up the rickety inside stairs. (Joe is so wraith thin he makes 85-pound me look like a bruiser. Liz McCann weighs upwards of 200 pounds.)

Throughout the first act Albee moaned, groaned and held his face in his hands as if in great pain. He was particularly anguished whenever the Jenny character had lines. As he and Liz McCann were exiting at intermission, passing in front of me to do so, I whispered to Liz that the restrooms were yet another flight of stairs below those we’d so recently and painfully navigated. She just smiled. She knew what I didn’t—that she and Albee were leaving. He was walking out on his own play.

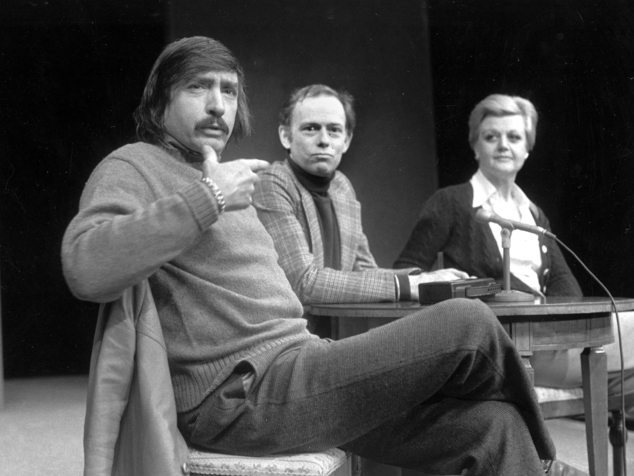

FILE – In this Jan. 27, 1977, file photo, playwright Edward Albee, left, makes a point as director Paul Weidner, center, and actress Angela Lansbury look on during a news conference in Hartford, Conn. (AP Photo/File)

What had made him so wretchedly unhappy, I learned later, was the failure to convey the humor, the black humor. The actress playing Jenny was a respected Method actress from a family steeped in Method acting. But Method acting does not readily lend itself to comic timing. (The actress of whom he so disapproved later changed her name.) Now he might have blamed the director in equal measure but chose to ignore him. Perhaps this was because the actress playing Mrs. Toothe, Kathleen Butler, was so splendid she got the director off the hook.

A couple of years later at The National Arts Club where Edward Albee was receiving yet another Medal of Honor, Howard Kissel formally introduced me to Albee—who, after identifying me as the women sitting two seats away from him—proceeded to rail about “that production” and “that dreadful actress.” He was still angry.

Addendum: The National Arts Club Medal of Honor being presented by the Literary Committee was for the Edward Albee Foundation. Albee had already received one for his own work. The Edward F. Albee Foundation exists to serve writers and visual artists from all walks of life, by providing time and space in which to work without disturbance.

When Howard Kissel introduced me to Albee, Albee looked at me quizzically, trying to recall from where he knew me. When I prompted him, mentioning the reading, it proved to be the fuse that set off the fury. He was still fulminating when he was dragged to the podium.

(Given that Albee died, sadly, with no survivors, his longtime partner having predeceased him, it’s likely that much of his estate will go to the foundation.)