by Samuel L. Leiter

A wall is very much in the news these days; however, the crumbling, vine-covered one that fills the upstage area in the New York premiere of Robert Holman’s Jonah and Otto—which debuted in Manchester, England, in 2008—has nothing to do with immigrants. Instead, it seems, oddly, to symbolize the need of a lonely vicar, who lovingly places his hands against its sunbaked bricks to find the warmth so lacking in his life.

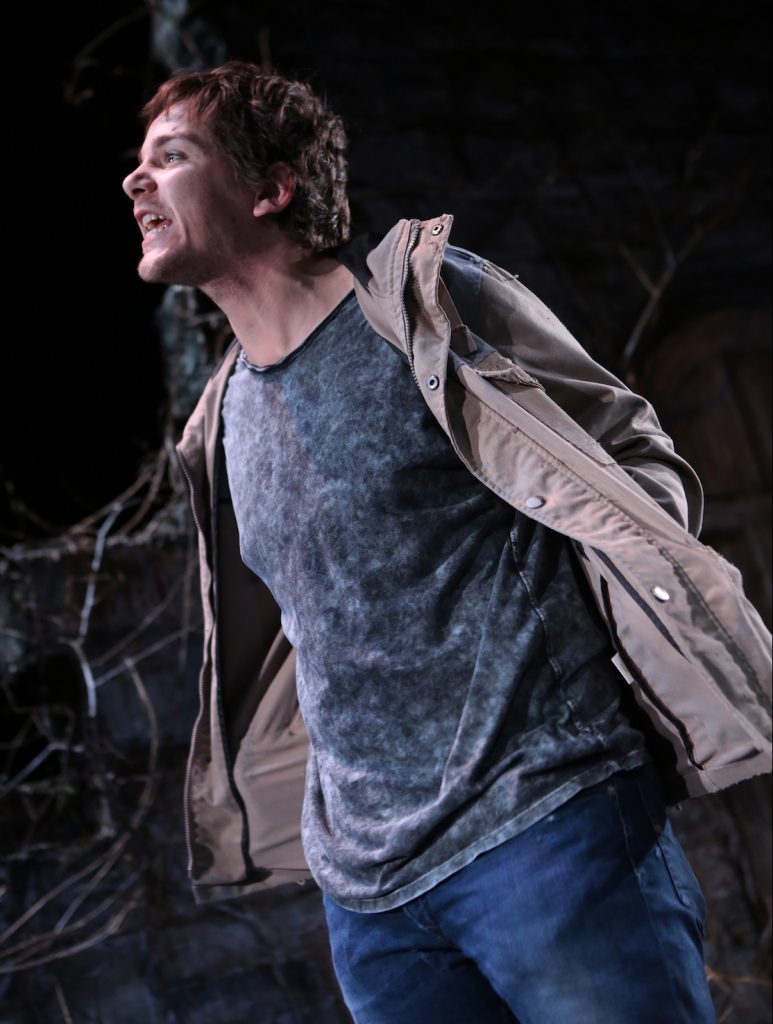

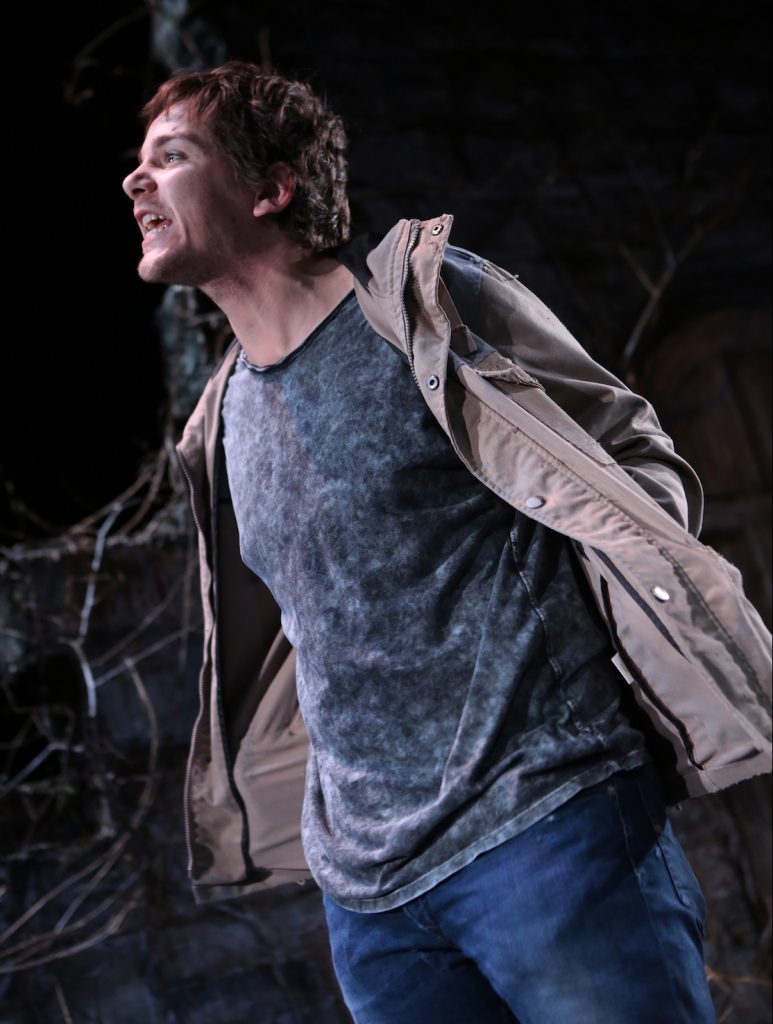

The wall (designed by Ann Beyersdorfer), which holds a large, wooden door, is part of a seaside public garden on the East Sussex coast, where the white-haired Otto (Sean Gormley), in his 60s, seeks solace. Into the garden enters a shabby, working class-accented 20-something named Jonah (Rupert Simonian), accompanied by a shopping wagon whose assorted cargo includes his six-week-old daughter.

With the only thing to sit on being a bench, the initial confrontation—during which a knife appears—suggests we might be in for a tense encounter along the lines of Albee’s Zoo Story. While what ensues does have Albee overtones, the atmosphere also suggests a bit of Beckett and Pinter.

Over the course of 90 intermissionless minutes, Otto and Jonah engage in thinly plotted talk, sometimes colorfully realistic and even vulgar, sometimes tediously elliptical and metaphorical. They talk of their mutual fears, doubts, insecurities, sexual and romantic experiences, personal tragedies, beliefs (or disbeliefs) in God, and the need for love. They note their differences and similarities, and the need to listen, to pay attention. A father-son relationship gradually blossoms. Symbols (like the wall) abound, like the apples and oranges that play a significant part in the action.

Jonah, at first, appears to be a fast-talking trickster, using sleight of hand to pilfer Otto’s money. Otto seems not only willing to have his money taken, but gradually begins giving it to the younger man, who, on several occasions, suffers epileptic fits. The tug and pull of their dialectic eventually sees something of a reversal in their roles as when, in an extended sequence, the light-fingered Jonah strips the sleeping cleric of his garments and dons them himself. Otto, stripped to his skivvies, eventually dons Jonah’s garments to complete the transference. Ironically—and perhaps costumer Katie Sue Nichols is responsible—Jonah couldn’t wear Otto’s clothes more frumpishly, while Otto actually looks coolly fashionable in Jonah’s grungy castoffs.

Both Gormley and Simonian give reasonably believable performances (especially the latter’s seizures) but Geraldine Hughes’s direction is dully mundane. Holman appears to be casting an allegorical cloak over his everyday characters, whose interactions, for all their ordinariness, often have about them a mystical, unrealistic hue that is absent here.

A more atmospheric staging along with more nuanced performances might ameliorate such disconcerting things as having the vicar, after his initial embarrassment, continue a lengthy scene in a public place while wearing nothing but socks, boxer shorts, and a t-shirt. And nothing in lighting designer Kate Bashore’s design captures such potentially impressive directions in the text as: “The earth is being lit by the setting sun. The sky is a fireball of red and yellow.”

Jonah and Otto, while nowhere near Albee’s Peter and Jerry, is a minor piece in search of major direction and design to fully bring its subtle colors into view.

Jonah and Otto. Through February 25 Lion Theatre/Theatre Row 410 West 42nd Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). www.theatrerow.org/lion-theatre

Photos: Davidawa Photography