Book review by Samuel L. Leiter

Casual notes on show-biz books, memoirs and studies, dust gatherers, and hot off the presses.

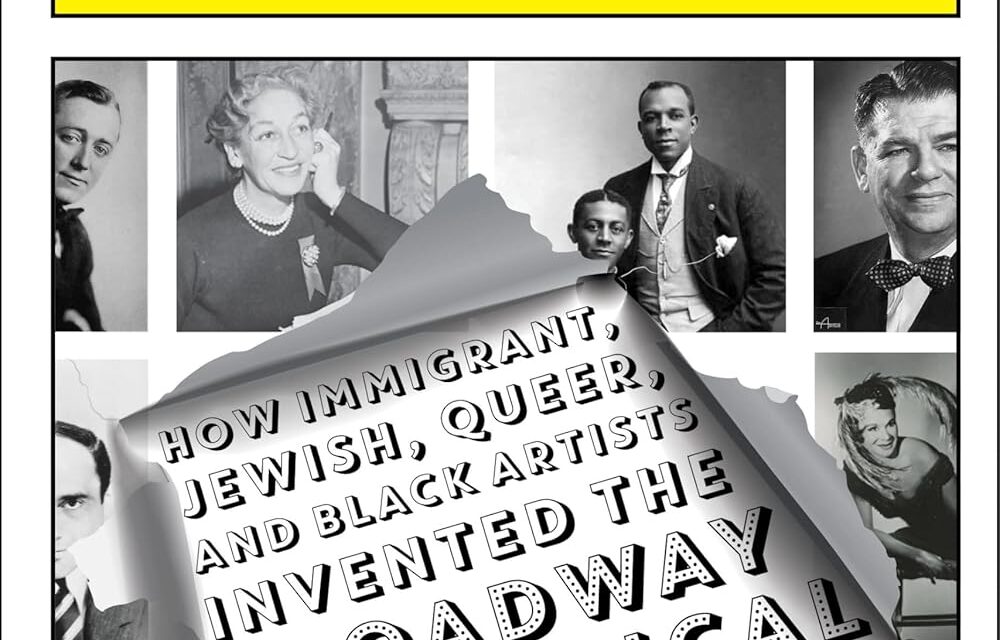

David Armstrong. Broadway Nation: How Immigrants, Jewish, Queer, and Black Artists Invented the Broadway Musical (Methuen/Drama: London, New York, 2025). 431pp.

I have mixed feelings about David Armstrong’s Broadway Nation, an impressive but flawed contribution to the never-ending succession of valuable books about the American musical theatre. Aimed at a wide audience of academics, students, and general readers, it’s a comprehensive historical survey of its subject, taking us from the musical’s 19th-century origins to just last year, when it went to press.

Broadway Nation’s major thematic raison d’être, as its lengthy subtitle indicates, is to frame the Broadway musical as a theatrical genre created largely by Jewish, immigrant, Gay (Armstrong, oddly, capitalizes it), and Black artists. In the text, however, women also get focused treatment. However, its examination of these categories can’t dig too deep, given the sweep of the narrative; often, in fact, the book ignores its thematic subtitle for what is more evidently its task, i.e., a recapitulation of the American musical theatre’s history and development, a goal, naturally, that requires the inclusion of many artists, like George Abbott or Agnes DeMille, to cite just two, who don’t fall into any of the named categories.

Of course, it’s no news that these categories are disproportionately responsible for the creation of the Broadway musical genre. Book after book has drilled this mantra into our heads, and there’s a small library of books devoted to each of these areas. In fact, despite a “selected bibliography”—a bit too “selected”—it’s surprising that Armstrong overlooks at least 13 major books on the contributions of Jews and gays; he’s better when it comes to works about African American contributions.

The immigrant experience as related to Broadway musicals’ creation—outside those of the Jews of the early 20th century—is the least well-covered by outside sources, although Armstrong does make use of Warren Hoffman’s narrow racial approach in The Great White Way: Race and the Broadway Musical, one of the few dealing seriously with immigration. Armstrong also omits mention of several classic Broadway musical history sources, among them the prolific output of Ethan Mordden, citing only his When Broadway Went to Hollywood and ignoring even his Gays on Broadway

Regardless, once the historical premises for each of the groups’ involvement is established, their participation becomes largely limited to having their ethnic background, immigrant connection, or sexual orientation mentioned in passing, I’ve never been sure, for example, about why so many assimilated, well-off Jews became musical theatre artists, as opposed to those like immigrant Irving Berlin, who had few other outlets for their talents.

Armstrong’s main business, as noted, is to describe the overarching history of the Broadway musical, and, while dropping references as to who fell into one or more of his categories, to discuss various thematic threads he finds running through the shows. For some artists, however, who fit his groupings, he overlooks their suitability. Two major Broadway composers are given as Jewish, but their gayness is ignored, although there’s no question Armstrong is aware of it. He is helpful at isolating trends, like nostalgia or social concerns, and at defining the different kinds of shows, like revues and jukebox musicals.

Nonetheless, serious fans of American musical theatre will not find much here not thoroughly covered elsewhere, although they’ll appreciate the compact way Armstrong has put it all together. On page after page, for example, they’ll find material presented in gray-backgrounded boxes written like encyclopedia entries, often giving the tome the feeling of a reference work or textbook, for which it would serve very well.

While necessarily selective, he covers most of the significant shows readers should know about. Having recently reviewed Cary Ginnell’s Carefully Taught: American History through Broadway Musicals (2022), I found it interesting to see Armstrong’s handling of similar material in his closing chapters, where he offers quality discussions of things like “Equity, Social Justice, and Inclusion” in musicals, although Ginnell’s book is not among his resources.

For those following Armstrong’s categories, he introduces many segments with initials to clarify the material’s reflection of his purpose: I=immigrant artists; J=Jewish artists; Q=Queer artists; B=Black artists; W=Women artists. The last named is not part of his titular concerns, but could have been since he has significant things to say about female contributions to musical theater. Also, his allusion to queer artists must be speculative at times, of course.

There is an enormous amount here to digest, so I can only hint at the contents by pointing to Armstrong’s division of Broadway musicals into the historical groupings he calls “The Genesis Period,” beginning in the 19th century, when minstrelsy, operetta, and vaudeville were popular; “The Silver Period,” from the 1920s through the 1930s, with an intermission for 1943’s Oklahoma!; “The Golden Age,” taking us through the 1940s and 1960s; and ending with “The Modern Era.” Aside from those who contributed outside Armstrong’s major concerns (see below), few leading I, J, Q, B, or W contributors get overlooked, as it’s as easy to name such musical theatre greats as it is to boil water: Berlin, the Gershwins, Blake, Porter, Weill, Youmans, Merman, Fields, Comden, . . . It goes on forever.

Even with its technical flaws—some of which I’ll get to—Armstrong’s book should be on the shelves of all Broadway musical lovers. If you’ve heard his “Broadway Nation” podcasts you’ll know you can trust his knowledge, his insights, and his accessibility. His writing is crisp, clear, and well documented. There’s also a decent gallery of over 50 b/w images and an index. What’s seriously lacking, and—as a victim of it myself—is the lack of a decent proofreader.

There are too many typos (like “guilt” for “gilt,” or Wintergarden for Winter Garden) misspellings of famous names (Lindberg for Lindbergh, Callaway for Calloway, Haywood for Heywood, Abrea for Abriea, Sweeny for Sweeney, and others.). One of the more notable bloopers declares that John Kander was born in Kansas City, Michigan. Another is accepting a critic’s claim that 1931’s The Band Wagon saw the first use of the revolving stage, which was born in Japan in the 1750s, and came into use in the West in the mid-1890s. And, as per its title, isn’t In the Heights set in Washington Heights, not neighboring Inwood? The average reader will likely overlook or miss many of these missteps; critics, however, have an obligation to note only them, even when guilty of them themselves (as I’ve been).

Armstrong’s broadly inclusive brush can lead to imbalances. He covers major choreographers, and choreographer-directors, not to mention dance arrangers, chiefly Trude Rittman, but only a tiny cohort of non-choreographing directors, like Josh Logan and Hal Prince; female (but not male) lighting designers (but no set or costume designers of either sex); several outstanding star performers, mainly Ethel Merman and Mary Martin, but few leading men (Alfred Drake, where are you?); and so forth.

Ultimately, Broadway Nation is a book whose virtues and shortcomings are inextricably intertwined: its sweep is admirable, its intentions honorable, and its utility considerable, even as its execution can be uneven and its scholarship occasionally blinkered by omissions, imbalances, and avoidable errors. Armstrong’s command of the musical theatre canon is genuine, and his ability to synthesize vast amounts of material into an accessible narrative will make the volume indispensable for newcomers and a handy compendium for seasoned devotees.

Readers seeking deeper analysis of the very groups the book aims to foreground—or those sensitive to the niceties of accuracy and emphasis—may find themselves alternately enlightened, exasperated, and wishing for a tighter editorial hand. Still, in a field where comprehensive overviews remain perennially welcome, Armstrong’s contribution earns its place, offering both a reminder of the rich, multivocal traditions that shaped the Broadway musical and an invitation to continue interrogating the stories we tell about its creation.