Review by Stuart Miller . . .

The Brothers Size is a transportive meditation on siblings, the way they can (and can’t) protect or hurt each other and on how if you live with your head in the clouds and can’t see yourself clearly you’ll always be vulnerable to being used.

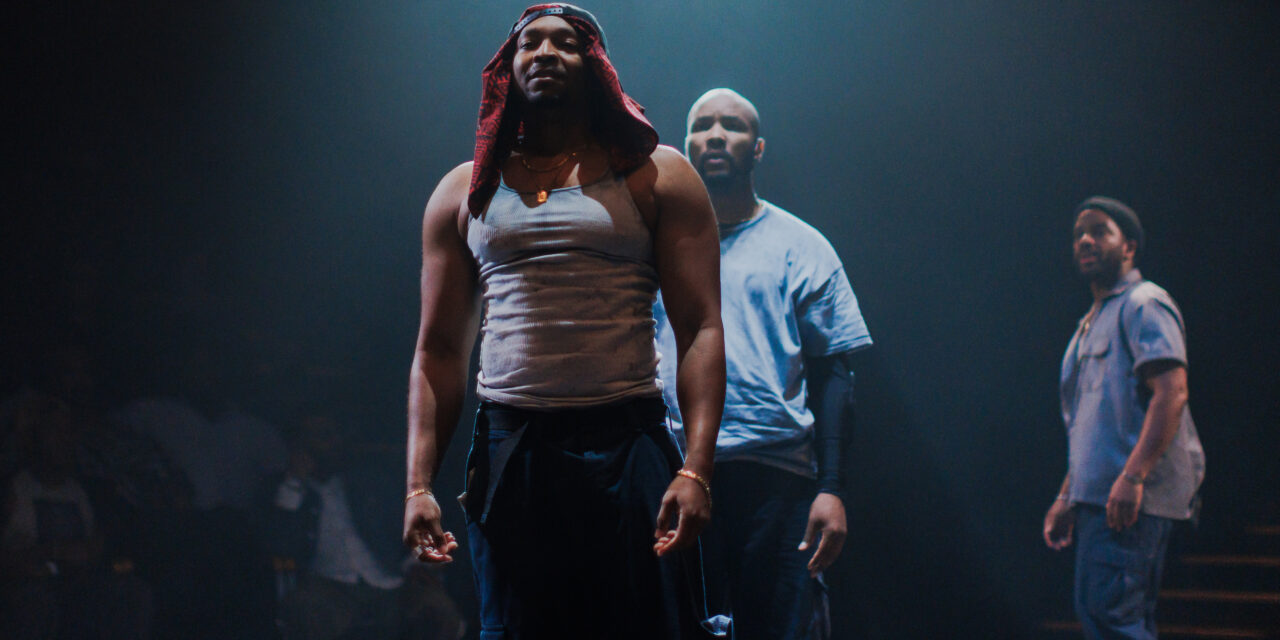

That it’s such a magical experience is a testament to the show’s creators because there is much that could go wrong with a play that wholly embraces its artifice: There’s no set or props, the actors often state their stage directions aloud, and the story is heavily reliant on percussion and choreographed almost dance-like performances.

Playwright and co-director Tarell Alvin McCraney’s writing is frequently beautiful but the story is straightforward. What creates the magic is how that artifice illuminates eternal truths, which is fitting because McCraney drew on stories and icons from Yoruba mythology. (McCraney’s co-director is Bijan Sheibani.)

Ogun Size (Andre Holland) is the hardworking older brother, who runs his own auto mechanic shop in the Louisiana bayou region. (In Yoruba, Ogun is a deity of both iron and labor, among other things.) Oshoosi Size (Alani iLongwe) is the carefree dreamer, the younger brother who always stumbles into trouble without regard for consequences. Ogun helped raise him after their mother was ill and then died but he couldn’t save Oshoosi from prison. Oshoosi is newly released and fantasizing of faraway places and women while Ogun is determined to teach him a work ethic.

McCraney perfectly captures the fraternal dynamic, mixing love and teasing and long-simmering feuds and resentments. At one point Ogun starts to sing and Oshoosi, who has a phenomenal voice, groans and mocks his singing.

Ogun is incredulous and defensive, saying “I use to sing you to sleep,” to which his baby brother retorts, “No, I use to close my ears until I passed out.”

Complicating things is the arrival of Elegba (Malcolm Mays), who was Oshoosi’s best friend– and maybe more– behind bars. Elegba (a trickster in Yoruba) genuinely seems to care for Oshoosi and yearns for more than friendship, but even as he calls Oshoosi “brother,” it’s clear that he puts his own wants and needs first– unlike Ogun’s and Oshoosi’s, theirs a breakable bond, especially if that tie becomes inconvenient or dangerous.

The stage is bare except for a circle of white substance that initially delineates the brothers’ home but also is a reminder of how each of them is trapped in their own way. That the white outline resembles cocaine is probably no accident either.

When the actors recite their stage directions it both gives them ownership of their actions (important for Black men in America, especially for those who have been incarcerated) and reveals to us their mood or intent in ways the dialogue might not. When Elegba calls Ogun “Size number 1,” Ogun says to the audience with disdain and frustration, “Pissed at being called Size number 1” before speaking to Elegba.

Finally, the rhythmic movement– enhanced by drummer Munir Zakee at the side of the stage– beautifully captures the characters’ push and pull tension. Ogun strains to protect and guide his brother– without acknowledging the futility of trying to change Oshoosi’s nature– while his brother floats toward his unrealistic ideas and Elegba seduces him, promising shortcuts to happiness that are anything but.

The writing and directing of these flourishes only work because the cast is so good. Holland, a versatile actor who played Elegba in a 2009 production, is weary and wary– he loves his brother but he also knows Oshoosi better than Oshoosi knows himself. iLongwe’s careless exuberance as Oshoosi is a perfect contrast. Mays (who occasionally swallows some words or lines) is vibrant and winning as Elegba, so we understand what Oshoosi sees there– Mays seems sincere in his emotions even as his behavior betrays that sincerity.

The play brims with humor and energy in the early going even as each of the three bristles at the ways they feel put upon. Then the inevitable happens– Oshoosi makes a bad choice, or rather he doesn’t make any choice at all and just exuberantly coasts into trouble– and Ogun turns his full fury on his reckless, hapless brother.

But Ogun also listens and has deep, often unspoken reservoirs of caring and compassion. McCraney, who wrote this as part of a trilogy of plays but is best known for co-writing the Oscar-winning “Moonlight” screenplay, withholds much of their family history until near the end when its revelation has a greater impact, when you see why they’ve been fighting each other and what they’re fighting for.

The ending is bittersweet because you just know it will not turn out the way the brothers hope it will. It may seem too quiet and anticlimactic for so passionate a play, but it feels like the only way out. But before that moment there’s a joyous and cathartic scene where Oshooshi performs Otis Redding’s “Try A Little Tenderness” with Ogun playing air organ and air drums as the brothers dance around their confining circle. It gives a glimpse of what could have been. If only. But no.

The Brothers Size is playing at The Shed, 545 W. 30th Street, through September 28th. It runs 90 minutes with no intermission. For further information, please visit: https://www.theshed.org/program/445-the-brothers-size

Photos by Marc J. Franklin.

Headline photo: Malcolm Mays, Alani iLongwe, and André Holland.