An impossible memorial for an unknowable man

By Jordan Cohen

“Whatever the truth is, the telling of it is inadequate,” declares the actor playing Lars Jan in The Institute of Memory (TIMe), written, directed, and designed by Jan himself, and currently in performance at the Public Theatre’s Under the Radar Festival. Delivered with equal parts hope and defiance, frustration and acquiescence, this brief moment captures perfectly the strength of will – not to mention, high-tech wizardry – required to tell a story that is, ultimately, impossible to tell.

In this 80-minute performance piece, Jan, a transmedia artist and Artistic Director of Early Morning Opera, presents complex themes centered on truth, privacy, memory, and surveillance, filtered through his attempt to piece together, with exacting fortitude, the life of his father Henryk, an inscrutable Polish WWII survivor turned McCarthy-approved operative. The title of the play is a reference to Warsaw’s Institute of National Memory, where Jan spent time gathering military documents, medical records, and secret surveillance files about his politically active, anti-Communist father (the piece uses both written text and text compiled from documents stored at the Institute).

Through nonlinear and technologically mediated enactments and reenactments of the past, we learn much about Jan’s endeavors to understand his father. We also learn a bit about Henryk, himself: after he escaped torture and imprisonment in Poland, he fled to London and then to Boston where he met his wife, who would eventually leave him and take their young son with her. We learn of Henryk’s involvement in McCarthy-era espionage and of Jan’s monthly visits with his father between the ages of 4 and 14 – cold and meaningless interactions, which Jan mines for meaning nonetheless.

“I lived the Twentieth Century, that you read about, that you watched moving pictures about,” proclaims Henryk. But Jan is not interested in the century as told in movies and books; instead, he attempts to decipher his father’s experiences – experiences that perfectly encapsulate the horrors of the century – so that he can better understand his father’s paranoid obsession with privacy, constant fear of surveillance, and his eventual diagnoses of dementia (Jan doubts this diagnosis and shows us projections of his brain scans, as if to prove his point).

But the task ultimately proves insurmountable: the records are too thin; Jan and Henrik’s encounters are too rare and unrevealing; Henryk is too impenetrable, private, in hiding long after anyone cared to pursue him. “Many men controlled the rest of us – they still do,” explains Henryk, who prefered to live and die anonymously, unknowable until his last day, even to his son.

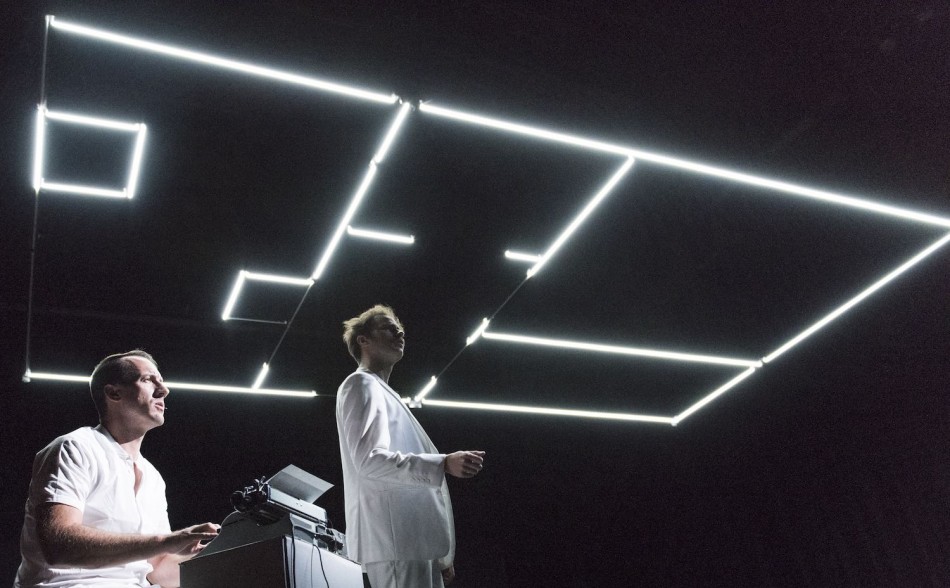

Dressed in eye-popping white suits (costumes by Kate Fry and Stephanie Petagno), Andrew Schneider (Jan and others) and Sonny Valicenti (Henryk and others) perform their roles with expert variety. In an early scene, they display great comedic timing as Jan’s relatives in Poland, and in other moments, they deliver highly poetic, if somewhat puzzling, dialogue with masterful skill. In many scenes, they adopt a Brechtian air, humorously announcing their characters as they switch from one snippet to the next (“I’ll be the brother.” / “Ok, I’ll be the sister.”). Valicenti portrays Henryk with ample chilliness and Schneider often narrates directly to the audience, laying bare Jan’s points of view, states of mind, and emotional reactions at various parts of the story. This technique offers a stark and welcome contrast to Henryk’s frustrating opacity.

The ambitious technological collaboration is nothing short of extraordinary (lighting: Christopher Kuhl; scenic: Jan; audio/vocal: Mariana Sadovska; sound: Nathan Ruyle and Mikaal Sulaiman; video/interactive software: Pablo N. Molina and Ting Zhang; animation design: Zhang). A large, structural LED light grid rotates throughout the space, providing both illumination and architectural variation on an otherwise bare stage. The actors walk under, above, among, and between the glowing bars, often as if emerging and coalescing, like a memory, from a hidden and radiating cortex of the brain.

Three-dimensional, digitally generated projections and animations – of human forms, homes, words, years, archival materials, medical scans – materialize then vanish, ghostlike, before our eyes. A rich, layered soundscape of experimental music and aural peculiarities, live and recorded, permeates the production. Most exciting, perhaps, is the “interactive typewriter,” which Henryk types on as he speaks dialogue adapted (presumably verbatim) from communications attributed to the real-life Henryk. Incredibly, the typewriter keys also control specific audio and lighting cues, endowing the deceased Henryk with an eerie sense of agency in the storytelling as his typed words give literal form to certain design elements in the production.

The pitfalls associated with developing a performance piece about a man so hidden in the shadows might be, for many, too difficult to overcome. But for our bravest and most inventive theatrical storytellers – including Jan, his team of designers and technicians, and his two actors – the challenge proves impossible to resist. In fact, incompleteness itself – of memory, of archive, of lived experience – provides the very thematic fodder that makes TIMe so fascinating (The Public Theatre’s Fun Home is another heroic example of a play that does exactly this).

Jan desperately wants to know, and tell us, the truth: the truth of his past, his family’s legacy, and his father’s life. But instead, he conveys a journey toward knowing – an improbable journey with an impossible outcome – reconstructed with memories of lives relived, reconjured, and restored.

*Photo: Lars Jan

The Institute of Memory (TIMe), Created by Early Morning Opera

Under The Radar Festival at the Public Theatre – Martinson Hall

425 Lafayette St, New York, NY 10003

Running through 1/17

Tickets: www.publictheater.org or call 212-967-7555