by: Michael Bracken

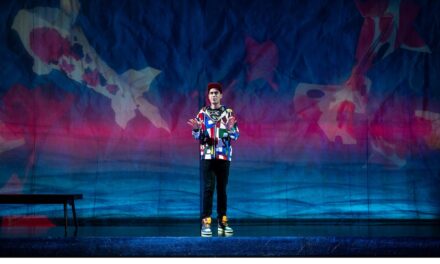

An unidentified war in an unnamed country, with undefined enemies and uncertain rules. Unspeakable acts mandated by anonymous authority, with no one to trust. Welcome to the world of Tara (Lindsey Kyler) and Oliver (John Clarence Stewart) in Tom Diggs’s Kind Souls at Shetler Studios.

Sound familiar? Variations on the theme have certainly played out in various media, and whenever they do, a question arises as to what the author is trying to say. War is hell? Ditto for peace? Meet the new boss, the same as the old boss? Or is it just a case of good old-fashioned existential angst?

Not that a drama needs a universal theme or a profound pronouncement. But it would be nice to know why we’re being asked to sit through ninety minutes of an intentionally vague struggle that goes nowhere, even if going nowhere is the point.

Of course, the same question could be asked of just about any play, including various surreal-tinged works of Edward Albee and absurdist masterpieces like Waiting for Godot. But Albee uses humor, decidedly absent from Kind Souls, to lighten the load, with characters often as absurd, or nearly as absurd, as their circumstances.

Godot surrenders completely to the void. Kind Souls doesn’t come close to making the leap. Nor does it reconcile its abstract elements with its flesh and blood characters. Neither fish nor fowl, it’s too nebulous for real connection and too personality-driven to justify its reticence.

Tara and Oliver live in the middle of the woods, unemployed, with no visible means of support. Tara is recovering from an unspecified injury or illness. They forage the forest floor for a semblance of food and talk about jobs, the “conflict” and Oliver’s upcoming birthday party. But nothing features in their conversational exchanges more than “they,” they being an amorphous and seemingly totalitarian source of power and fear.

When Tara sees smoke on the other side of the forest, she takes it as a sign that jobs may be forthcoming. And sure enough Oliver is soon employed, working for “them” in some sort of cleaning capacity. He reeks of some acrid odor when he gets home at night and once has blood on his clothing. He refuses to give Tara any details of his job, claiming he’s sworn to secrecy. The couple’s standard of living improves a bit: they have money and real food.

Tara wants to work as well, but Oliver says she’s too fragile. Still, she eventually finds a job, with “them” of course, and learns what Oliver does. It isn’t pretty.

Diggs is not without talent. His characters are well-drawn and his dialogue credible; he successfully creates a sense of menace. But his vision of the bigger picture is cloudy. The play’s story arc is not an arc at all: it’s as flat as Kansas. Atrocities are committed; howls are emitted; the couple fights and makes up. A war ends, for God’s sake. But in their alternate universe, Tara and Oliver remain distant and inaccessible. Emotions vary from anger to intimacy, but the tone remains constant. There is no there there. And if by some chance that’s the point, which is doubtful, it needs to be communicated more clearly.

Alexander Greenfield’s direction is efficient, but he hasn’t found a way to light a spark under this flame-retardant drama. It’s just not compelling. Kyler is appealing as Tara, displaying considerable range, especially at the play’s beginning. Stewart is solid as Oliver. Carl Wiemann’s lighting effectively creates mood throughout, even when the playwright doesn’t.

*Photos: Carl Wiemann

Kind Souls. Through February 1. Shetler Studios at 244 West 54th Street, 12th Floor, between Broadway and 8th Avenue. Tickets are $18, available at 347-352-4549 or www.libratheater.org