by Samuel L. Leiter

Playwright Rinne Groff (The Ruby Sunrise) rubs her dramatic sticks together vigorously in Fire in Dreamland, now at the Public after its world premiere at the Kansas City Repertory Theatre. The resulting sparks, though, set off no alarms.

Set mostly from March to October 2013, not long after the devastation wrought by Superstorm Sandy, the three-character play focuses on Kate (Rebecca Naomi Jones, Big Love), a single woman in her 30s, living in Coney Island. Kate works for a public/private partnership sponsored by Mad Burger (the video game, one assumes) that aims to redevelop the area in the wake of Sandy’s destruction.

Adrift romantically, emotionally, and professionally, Kate meets cute with a handsome, young Dutchman, Jaap Hooft (Enver Gjokaj, TV’s Dollhouse), a film school student bent on making a film (don’t say “movie” to him) about the horrific events of May 26, 1911. That’s when Dreamland, one of Coney’s famous amusement parks, burned down. His chief focus is on filming the efforts to save the park’s menagerie of animals, among them a group of Shetland ponies, a baby elephant, and, especially, Black Prince, a lion who met a remarkably dramatic end.

Kate—finding in the exciting project the meaningful fulfillment she’s dreamed of but that’s escaped her—becomes seriously involved with both the film and Jaap, as well as with Lance (Kyle Beltran, Gloria), Jaap’s nerdy film school colleague and assistant.

To accommodate the play’s highly episodic structure, Susan Hilferty (who also did the fine costumes, especially a mermaid dress) has provided a neutral, thrust-stage set of boardwalk-like planking, serving for both Kate’s apartment and exterior scenes.

Kate and Jaap engage in an on-again, off-again relationship as Jaap contends with multiple financial, creative, and personal issues, including his visa status. Lance’s professional and personal participation—including his adding a soupçon of sexual ambivalence—provides the triangle’s third leg.

Kate, unable to conjure her own dream of making a meaningful contribution to the world despite her multiple degrees, hitchhikes on Jaap’s. He, however, regardless of his talent—or what we’re told of it—comes off as a superficially charming but ultimately self-serving con man, a pretender with delusions of grandeur, an artist who considers any compromise a sacrifice, and someone who expects everyone to abandon their dreams to follow his.

The essentially straightforward through-line is clouded by film script-like jump cuts facilitated via sudden lighting changes (well executed by Amith Chandrashaker). Each is signaled by the crack of a film clapper held by Lance, even when he’s just a silent observer sitting on the sidelines. Groff’s script indicates precise dates and times, separating some scenes by only a few minutes, others by weeks, months, or even years, but the audience has no way of knowing the rapid fire differences differences (Groff recommends avoiding explanatory titles), especially when they skip backward several years to a hospital sickroom. It’s an unnecessarily foggy device serving only to draw attention to itself while giving the play a patina of artistic self-importance.

Of the many unpersuasive scenes, those concerning Jaap’s allegedly awesome film are the greatest offenders. His few minutes of footage, we’re to understand, show little more than placid animals filmed surreptitiously at the zoo and then transformed by CGI experts in India into panicked beasts fleeing a raging fire. Even if this were possible, it suggests that Jaap is less a filmmaking artist than the CGI technicians. In fact, no explanation is ever presented of what, apart from the fire, Jaap intends to include in his scriptless film. Its very significance is left for the audience to ponder.

Each of the three actors offers a determined performance under Marissa Wolf’s brisk direction but, largely because of the writing, their characters never come to life. Gjokaj uses his star-quality looks and magnetism to good advantage, but his Dutch accent sounds Eastern European and he’s saddled with cutesy, phony-sounding “foreigner” dialogue and jokey, implausible misunderstandings that few actors could make convincing. A tiny sample comes when Kate says, “I’m playing hooky,” and Jaap innocently asks, “Hooky means masturbating?” Seriously?

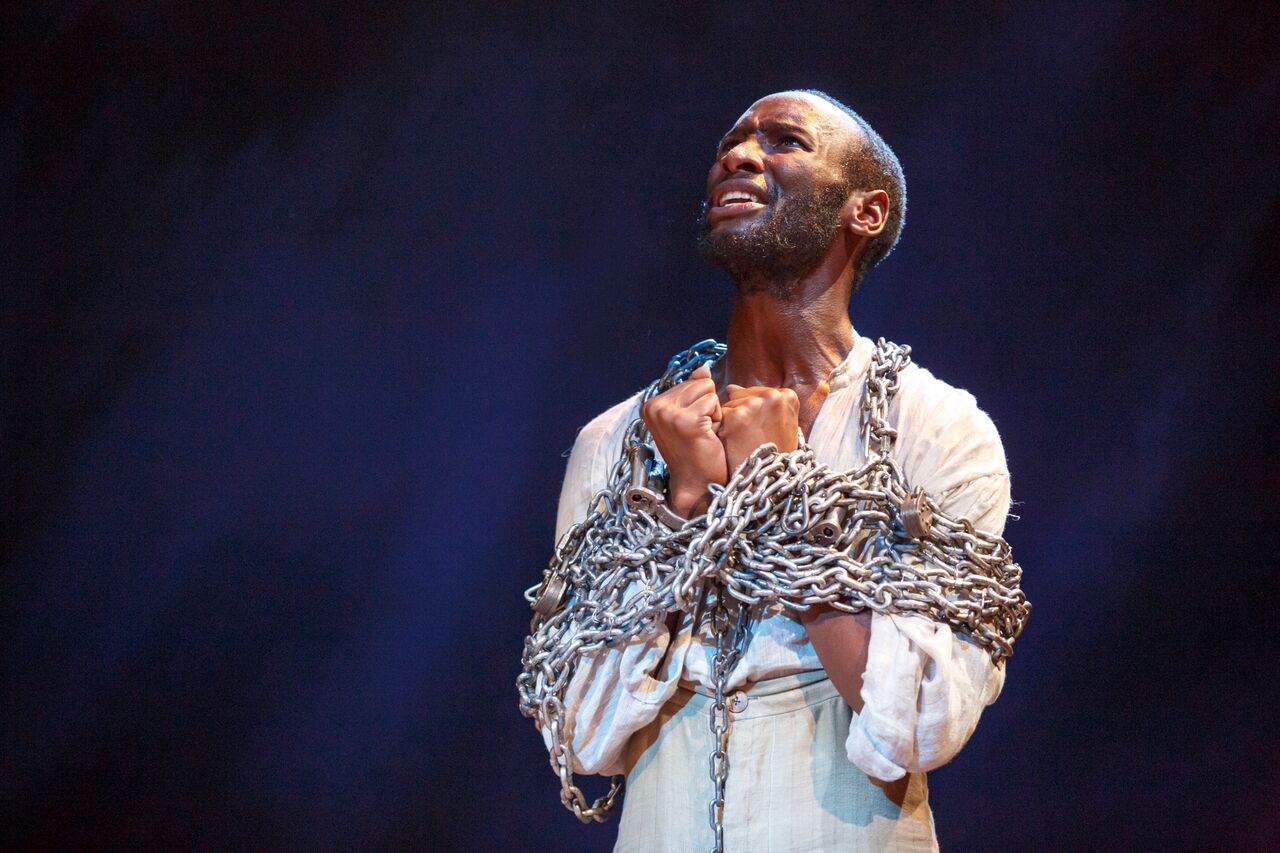

Jones is vitality itself as Kate. She accomplishes some technical feats outstandingly—like a very long monologue and a climactic bit where she explodes in a series of earsplitting leonine roars—but her Kate remains more flash than flesh. Beltran, the most restrained of the trio, does his best to make his vaguely crafted character three-dimensional.

Groff seems to be trying to connect Kate, Jaap, and Lance’s struggles to realize their dreams to the hopes for recovery of Sandy’s victims. Unfortunately, her playwriting smoke and mirrors quickly tamp down those Dreamland fires.

Fire in Dreamland. Through August 5 at the Public Theater’s Anspacher Theater (425 Lafayette St at Astor Place). www.publictheater.org

Photos: Joan Marcus