Sometimes in the world of theater reviews we stumble across the good fortune of having pieces by two different esteemed critics, allowing us to see comparative and contrasting viewpoints—always an intriguing experience. This is one such time and, if nothing else, the two pieces underscore the delights of Zero Hour. First, here’s our review from Samuel L. Leiter. For a review by Myra Chanin, please click here.

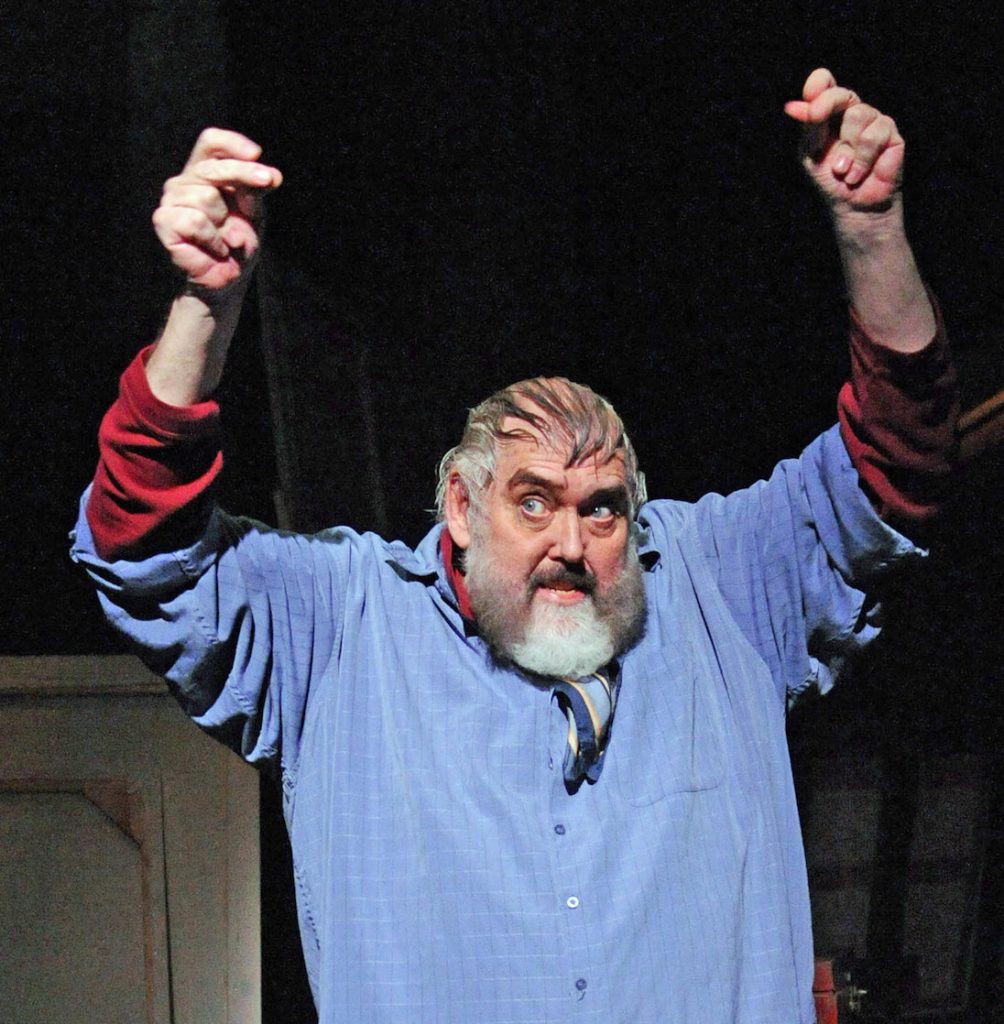

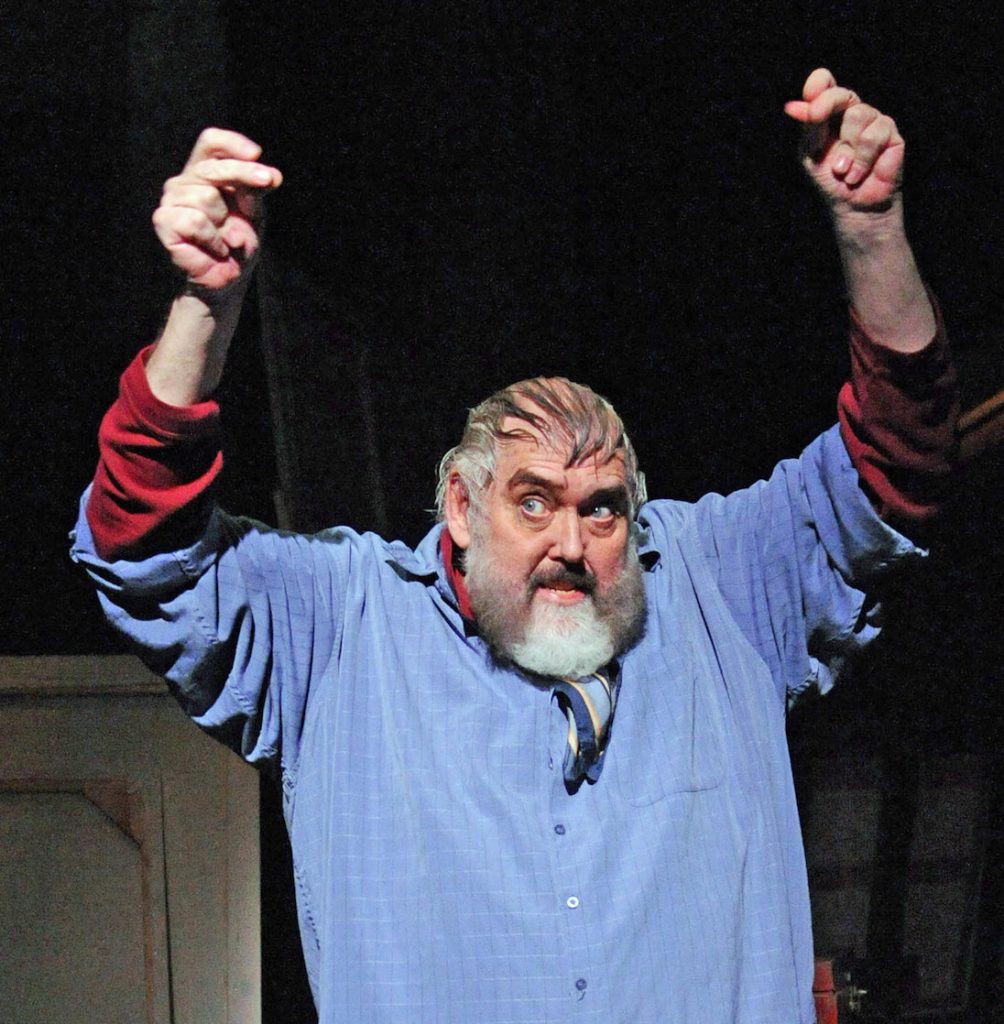

As the program cover photo for Zero Hour, Jim Brochu’s masterful, occasionally hilarious, hour and a half reincarnation of Zero (né Samuel) Mostel, reveals, the actor bears a striking resemblance to the late actor-comedian-painter. The grizzly beard, the balding pate with its desperate strands of surging, matted, combed-forward gray hair, the rotund face, and, best of all, the glowering eyes all come together to make Brochu’s punim about as close a replica of the original as you could wish.

On stage, he’s even more Mostellian, his burly body shuffling about—Mostel suffered a serious leg injury in 1955—in what Josh Iacovelli has designed to suggest (lots of empty frames hanging on the walls) the West 28th Street studio he kept to follow his obsession with painting, which he took more seriously than performing.

Brochu’s voice is a bit flutier than Zero’s boom box but it’s doubtful anyone could more accurately embody the larger-than-life physical and emotional essence of Mostel. I’m old enough to have seen him change without makeup into a bellowing rhino in Ionesco’s Rhinoceros in 1960, to have just missed his Pseudolus in A Funny Thing . . . in 1962 (I saw replacement Jerry Lester), to have caught his Tevye two years later in Fiddler on the Roof, and to have been crushingly disappointed when I didn’t get to view his Shylock in Wesker’s The Merchant in 1977; I had to settle for his overwhelmed understudy when the 62-year-old star died after only one performance.

This Peccadillo Theater Company revival of Brochu’s play, briskly directed by Piper Laurie (be still my teenage heart), in which he’s been touring since 2006 (it first played New York in 2009), uses a premise familiar from many similar one-person biodramas. Unlike those that have the character speak directly to the audience, it assumes that Mostel is being interviewed by someone, in this case from the New York Times.

Solo biodramas about long-dead writers (like Emily Dickinson or Charles Dickens) must recreate them mainly from literary sources, their personality and appearance being known more to specialists than audiences. Sometimes, the image created, like Hal Holbrook’s Mark Twain, seems so real we mistake it for the real thing. But when it’s a performer still alive in people’s memories, like Mostel, the actor must compete not only with such recollections but with the recordings, films, and videotapes on which the artist’s work and personality is permanently etched.

Mostel made few movies, by the way, but he scored highly in A Funny Thing . . . and The Producers, although Brochu/Mostel dismisses the latter while expressing bitterness about being overlooked for the cinema version of Fiddler by the casting of Israeli actor Topol, whom he ridicules as Topo Gigio.

Dressed in a blue artist’s smock, a bandanna around his neck, he rambles through his professional and personal experiences, tells us how he got the name Zero, roams about, answers the phone only to shout at the caller and shrug it off with a “That was my wife,” pontificates about art, sprays words like “putz” and “schmuck” about, drops names freely, and regales us with show business anecdotes.

At one point, though, when talking of his Brooklyn youth, he mentions Kings Highway and Pitkin Avenue as if they were connected; those places defined my own boyhood so I’d like to request Mr. Brochu, a Brooklyn boy himself, to check his geography.

A significant part of Zero Hour is spent on the communist investigations and blacklist of the fifties, which caused such agony and tragedy among left-leaning show biz figures, Mostel and his closest friends among them. Unable to resist a joke, he even wisecracked during his own interrogation, an episode he amusingly reconstructs, sitting at a desk behind a small lamp resembling a microphone as Congressman J. Parnell Thomas piles on the innocuous questions.

If you’re familiar with the iconoclastic Mostel’s life from having read, for example, Jared Brown’s biography or the book coauthored by Mostel’s wife, Kate, and Jack Gilford’s wife, Madeline, don’t expect to find anything new here, apart, perhaps, from one or two jokes (all are worth hearing again, though). If you don’t laugh, Mostel’s likely to charge you with having had “a humor bypass.” At one point he tries to justify his habit of breaking character on stage to improvise for laughs, a moment that doesn’t ring quite true if you speak to other actors who had no choice but to endure it.

Even those who already know this colorful rags-to-riches account of a poor Brooklyn boy whose father was a “street rabbi” and whose mother never forgave him for marrying a “shiksa”—or who don’t think they need yet another iteration of the blacklist saga and the naming of red-tinted actors by Jerome Robbins and his ilk—will appreciate the illusion of hearing about it all from Mostel himself. I mean Jim Brochu, of course, but when you’re watching him it’s really one and the same.

Zero Hour. Through July 9 at Theatre at St. Clements (423 West 46th Street, between Ninth and Tenth Avenues). www.thepeccadillo.com

Photos: Stan Barouh