An education of/for the revolution

By: Jordan Cohen

The Chilean playwright and director Guillermo Calderón was last represented at the Public Theatre with his play Neva, which muses eloquently on the nature of love, theatre, and the ego in pre-revolutionary Russia. Politics are mentioned only in passing until the end, when Masha, an actress, erupts with passionate condemnation of bourgeois decadence and greets, oracle-like, the coming revolution. The play is inspired by Chekhov and his widow, and much like Chekhov, Calderón allows his underlying message to arise in a single spurt, fleeting yet powerful, when subtext no longer suffices.

This strategy is thrown entirely out the window in Escuela, written and directed by Calderón and in performance now at The Public Theatre’s Under the Radar Festival. In Escuela, five people gather secretly on New Year’s Eve in a house in Santiago, Chile. They appear as regular folks, dressed in suits, blouses, skirts – but with one unsettling exception: the cloth, hood-like covering that completely conceals their heads, except for their eyes, for the entirety of the performance. Over the course of ninety-minutes, we observe a series of vignettes – classroom lessons – with each actor shifting between the roles of teacher and pupil, depending on the lesson at hand.

And what exactly is the course of study? Well, imagine a vocational school for Marxist revolutionaries and you’ll get the picture. There’s Poli Sci, with lectures on Marxist theory, worker solidarity, state corruption, and psychological warfare; there’s Shop Class, where, with disquieting placidity, students learn to construct and detonate a bomb; and then there’s Gym Class, where students gain highly physical experience with a firearm. We learn that through these lessons the characters are becoming incorporated into a larger counter-government operation. Anonymity provides safety in the event that a future operative is caught and interrogated.

Calderón strips the piece of all the markings of conventional theatrical narrative: there is no framing device or hidden theme; no subplot or subtext, exposition or resolution; no histrionic pronouncement to reveal the play’s hidden meanings.

Instead, there are only the lessons, dramatized seemingly without dramatization, staged with the objective eye of a documentarian. Music and singing is used, not as a theatrical device, but as a contribution to the character’s efforts to unite. Actors speak naturalistically (amplified well to accommodate the Public’s somewhat cavernous LuEsther Hall) and disregard the fourth wall. While the stage area is expansive, the production makes use of only a small area, center, about the size of, well, a modest living room in a city like Santiago. A table, two chairs, and a chalkboard, set upon a checkered wood floor, contribute to the makeshift classroom environment.

At times, the dialogue veers into the overly didactic, but since the pedantry is a function of the plot and not (solely) the playwright inserting his own viewpoints, it is easy to forgive. Indeed, didacticism has long been a hallmark of political theatre, and in Escuela, which fuses political theatre and documentary drama, education means not only political activation, but also historical understanding for us, the viewers.

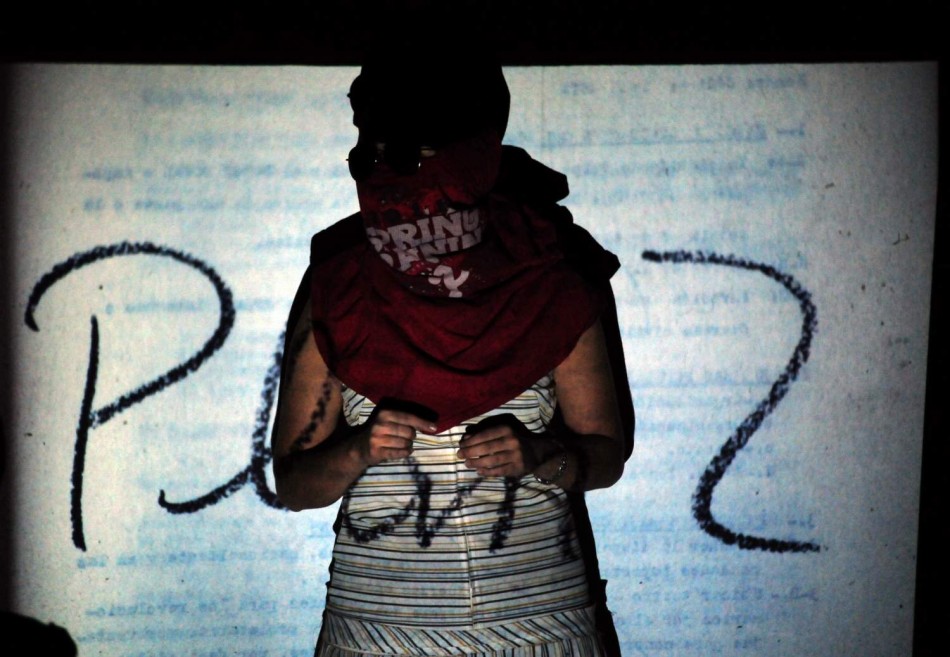

It is worth noting that the play’s events closely mirror Calderón’s own experiences in paramilitary training sessions decades earlier. Toward the end of the play, an image of Calderón and others painting a revolutionary slogan on a wall is projected onto the chalkboard. The photograph, taken in the late 1980s during Augusto Pinochet’s oppressive dictatorship in Chile (Pinochet remained a powerful figure until 1998), provides important historical contextualization and sharply increases the stakes of the preceding scenes. The enemy is no longer unnamed.

The actors deliver skillful vocal and physical performances. They are, at appropriate times, emphatic and tough, polite and affable, expressive and sympathetic. As an ensemble, they work smoothly and efficiently, and as individuals, they draw clear and complex characters, despite their concealed faces. They handle moments of levity with understated ease, for instance, when they discuss with matter-of-factness how to outrun a self-detonated bomb.

While these events in Chilean history might seem far from our own experiences (Pinochet and his regime unjustly imprisoned, murdered, and tortured countless citizens), perhaps a parallel or two can be drawn. In the final moment of the play, the characters chant, “Vote yes, vote no, same shit” in response to a rigged government referendum set for later in the year. While violent revolution is not the panacea for our broken democracy and inept leaders across the ideological spectrum, perhaps we can be inspired by the characters’ determination to retake their government, and in doing so, their lives.

Escuela

(Presented in Spanish with English supertitles)

Written and Directed by Guillermo Calderón

Design by Loreto Martínez and Musical Arrangements by Felipe Bórquez

Cast: Luis Cerda, Camila Gonzaléz, Andrea Giadach, Francisca Lewin, and Carlos Ugarte

Under The Radar Festival at the Public Theatre – LuEsther Hall

425 Lafayette St, New York, NY 10003

Running through 1/17

Tickets: publictheater.org or call 212-967-7555