By Stuart Miller…

Tim Blake Nelson’s play is a glimpse at where AI may be taking us.

An article in the New York Times Sunday cautioned that some AI experts believe we are just a few years away from the technology being capable of an uprising– unleashing a virus or corralling an army. In that light–but only that light– Tim Blake Nelson’s grimly fascinating new play “And Then There Were No More,” which also opened Sunday, feels almost hopeful.

In his future, humans have willingly– even happily, an official argues– ceded power to a “system,” one which emphasizes the proper function for every person and every situation. But at least we’re still out there living some kind of life, one that’s largely free of crime and violence.

There has, however, been a multiple homicide, an exceedingly rare event. And the woman (Elizabeth Yeoman) who killed her children, husband and mother (supposedly one-third of all murders in the city that year), has been deemed beyond rehabilitation. She is about to be executed painlessly by a new machine that will vaporize her out of existence but while the woman initially agreed to this sentence at the last minute she is seeking a different exit.

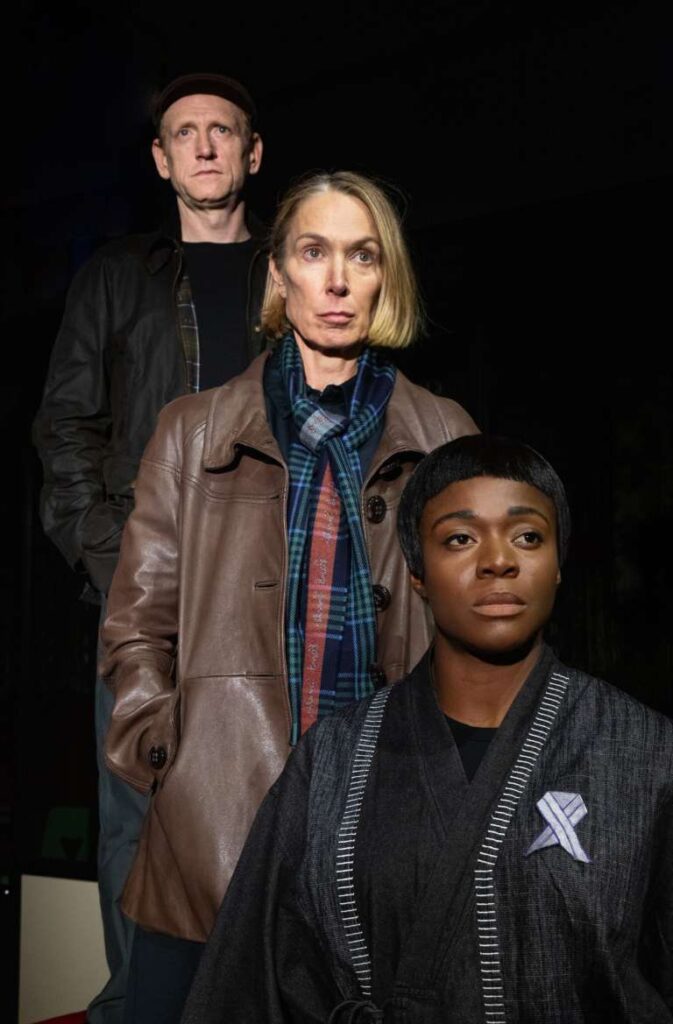

The official in charge (Scott Shepherd) has called in an attorney (Elizabeth Marvel) to represent the woman. The system deemed her the perfect candidate, he says, even though she has become burned out and not handled a case in a year. But while the official waxes rhapsodic about how the system has fixed society, it is clearly not flawless–the woman should not have been allowed to marry– but it cannot be argued with.

Once the attorney realizes what has happened– that the murderer had been operated on and tortured at a previous facility and that those with an investment in making this new machine work (Jennifer Mogbock) are in a hurry for a successful case she becomes an ardent advocate for her client. When she begins to argue her case, the lights come up and the audience realizes that we are the jury, implicated in whatever is about to happen.

To say more beyond that first half of the play would be to give away too much and if the system has decided I was the ideal person to review this play then it’s because it knows I won’t give away what happens in the trial or in the aftermath.

Suffice to say that Nelson does an effective job of drawing us into this situation and writes his way through it to an ending that’s not predictable but that, sadly, seems inevitable. Some of the ideas may seem familiar to fans of dystopian sci-fi but those concepts are usually found in the pages of novels or in TV and film; there’s an intimacy in a live performance– as when the audience becomes the jury– that enhances the story’s impact.

The actors (including Henry Stram as the man who serves the Machine) are all strong and director Mark Wing-Davey has overseen the creation of a set that is brutal and menacing and action that is well-paced.But while the play is often riveting and certainly thought-provoking in a terrifying way, it can also feel like it’s missing certain crucial elements. I used the word grim earlier because it is largely humorless (something one character says has become true of many people in that society, but that doesn’t excuse the playwright).

Additionally, we don’t get enough of a sense of what life outside this prison facility is like for people who live in this brave new world. Are there freedoms and joys as a tradeoff for what is sacrificed? The absence is especially notable because the official is quite articulate in his enthusiasms for the way the “system” has improved life: He justifiably shreds our current system for jury selection, which can often end up with the “unemployed” and the “bored” as those in charge of the fate of the accused. Now, he says, “the function for jury selection furnishes trials with the men and women uniquely suited to judge each specific case.”

As he lists other benefits of the system (including the lack of crime), you may briefly wonder if life is actually better in this world. Of course, the more he talks the more you realize how much control and free will has been removed and, as the attorney notes, justice has come to mean only retribution, not mercy or rehabilitation (which we can still aspire to or pretend we do now).

But when the attorney states her case before the jury, she pulls a classic lawyerly maneuver, finding a hole in the government’s position, an undeniable technicality and that undermines it all.

Legally, it’s her best play but since she is the stand-in for us, the fact that as a character she never gets full rein to argue on behalf of humanity in all its messiness.

Nelson has written a dark play that is chilling. The condemned has a line in the first act that is truly haunting and when the attorney echoes that idea in a different context in the second act it resonates powerfully. And I respect Nelson’s refusal to back down. But ultimately the play may be too cold and inhumane for its own good.

And Then We Were No More runs at La Mama, 66 East 4th Street through November 2nd. It runs just over two hours with one intermission.

Photo Credits: Bronwen Sharp